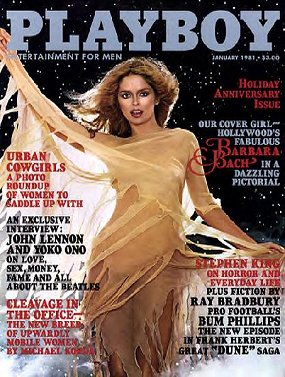

1980 Playboy Interview

With John Lennon And Yoko Ono

by

David Sheff

September 8-28, 1980

Published January 1981

A

candid conversation with the reclusive couple

about their years together and their surprisingly

frank views on life with and without the Beatles.

To

describe the turbulent history of the Beatles,

or the musical and cultural mileposts charted

by John Lennon, would be an exercise in the obvious.

Much of the world knows that Lennon was the guiding

spirit of the Beatles, who were themselves among

the most popular and profound influences of the

Sixties, before breaking up bitterly in 1970.

Some fans blamed the breakup on Yoko Ono, Lennon's

Japanese-born second wife, who was said to have

wielded a disproportionate influence over Lennon,

and with whom he has collaborated throughout the

Seventies.

In

1975, the Lennons became unavailable to the press,

and though much speculation has been printed,

they emerged to dispel the rumors -- and to cut

a new album -- only a couple of months ago. The

Lennons decided to speak with Playboy in the longest

interview they have ever granted. Free-lance writer

David Sheff was tapped for the assignment, and

when he and a Playboy editor met with Ono to discuss

ground rules, she came on strong: Responding to

a reference to other notables who had been interviewed

in Playboy, Ono said, "People like Carter

represent only their country. John and I represent

the world." But by the time the interview

was concluded several weeks later, Ono had joined

the project with enthusiasm. Here is Sheff's report:

There

was an excellent chance this interview would never

take place. When my contacts with the Lennon-Ono

organization began, one of Ono's assistants called

me, asking, seriously, "What's your sign?"

The interview apparently depended on Yoko's interpretation

of my horoscope, just as many of the Lennons'

business decisions are reportedly guided by the

stars. I could imagine explaining to my Playboy

editor, "Sorry, but my moon is in Scorpio

-- the interview's off." It was clearly out

of my hands. I supplied the info: December 23,

three P.M., Boston.

Thank

my lucky stars. The call came in and the interview

was tentatively on. And I soon found myself in

New York, passing through the ominous gates and

numerous security check points at the Lennons'

headquarters, the famed Dakota apartment building

on Central Park West, where the couple dwells

and where Yoko Ono holds court beginning at eight

o'clock every morning.

Ono

is one of the most misunderstood women in the

public eye. Her mysterious image is based on some

accurate and some warped accounts of her philosophies

and her art statements, and on the fact that she

never smiles. It is also based -- perhaps unfairly

-- on resentment of her as the sorceress/Svengali

who controls the very existence of John Lennon.

That image has remained through the years since

she and John met, primarily because she hasn't

chosen to correct it -- nor has she chosen to

smile. So as I removed my shoes before treading

on her fragile carpet -- those were the instructions

-- I wondered what the next test might be.

Between

interruptions from her two male assistants busy

screening the constant flow of phone calls, Yoko

gave me the once-over. She finally explained that

the stars had, indeed, said it was right -- very

right, in fact. Who was I to argue? So the next

day, I found myself sitting across a couple of

cups of cappuccino from John Lennon.

Lennon,

still bleary-eyed from lack of sleep and scruffy

from lack of shave, waited for the coffee to take

hold of a system otherwise used to operating on

sushi and sashimi -- "dead fish," as

he calls them -- French cigarettes and Hershey

bars with almonds.

Within

the first hour of the interview, Lennon put every

one of my preconceived ideas about him to rest.

He was far more open and candid and witty than

I had any right to expect. He was prepared, once

Yoko had given the initial go-ahead, to frankly

talk about everything. Explode was more like it.

If his sessions in primal-scream therapy were

his emotional and intellectual release ten years

ago, this interview was his more recent vent.

After a week of conversations with Lennon and

Ono separately as well as together, we had apparently

established some sort of rapport, which was confirmed

early one morning.

"John

wants to know how fast you can meet him at the

apartment," announced the by-then-familiar

voice of a Lennon-Ono assistant. It was a short

cab ride away and he briefed me quickly: "A

guy's trying to serve me a subpoena and I just

don't want to deal with it today. Will you help

me out?" We sneaked into his limousine and

streaked toward the recording studio three hours

before Lennon was due to arrive.

Lennon

told his driver to slow to a crawl as we approached

the studio and instructed me to lead the way inside,

after making sure the path was safe. "If

anybody comes up with papers, knock them down,"

he said. "As long as they don't touch me,

it's OK." Before I left the car, Lennon pointed

to a sleeping wino leaning against the studio

wall. "That could be him," Lennon warned.

"They're masters of disguise." Lennon

high-tailed it into the elevator, dragging me

along with him. When the elevator doors finally

closed, he let out a nervous sigh and somehow

the ludicrousness of the morning dawned on him.

He broke out laughing. "I feel like I'm back

in 'Hard Day's Night' or 'Help!'" he said.

As

the interview progressed, the complicated and

misunderstood relationship between Lennon and

Ono emerged as the primary factor in both of their

lives. "Why don't people believe us when

we say we're simply in love?" John pleaded.

The enigma called Yoko Ono became accessible as

the hard exterior broke down -- such as the morning

when she let out a hiccup right in the middle

of a heavy discourse on capitalism. Nonplused

by her hiccup, Ono giggled. With that giggle,

she became vulnerable and cute and shy -- not

at all the creature that came from the Orient

to brainwash John Lennon.

Ono

was born in 1933 in Tokyo, where her parents were

bankers and socialites. In 1951, her family moved

to Scarsdale, New York. She attended Sarah Lawrence

College. In 1957, Yoko was married for the first

time, to Toshi Ichiyanagi, a musician. They were

divorced in 1964 and later that year, she married

Tony Cox, who fathered her daughter, Kyoko. She

and Cox were divorced in 1967, two years before

she married Lennon.

The

Lennon half of the couple was born in October

1940. His father left home before John was born

to become a seaman and his mother, incapable of

caring for the boy, turned John over to his aunt

and uncle when he was four and a half. They lived

several blocks away from his mother in Liverpool,

England. Lennon, who attended Liverpool private

schools, met a kid named Paul McCartney in 1956

at the Woolton Parish Church Festival in Liverpool.

The following year, the two formed their first

band, the Nurk Twins. In 1958, John formed the

Quarrymen, named after his high school. He asked

Paul to join the band and agreed to audition a

friend of Paul's, George Harrison.

In

1959, the Quarrymen disbanded but later regrouped

as Johnny and the Moondogs and then the Silver

Beatles. They played in clubs, backing strippers,

and they got their foot in the door of Liverpool's

showcase Cavern Club. Pete Best was signed on

as drummer and the Silver Beatles left England

for Hamburg, where they played eight hours a night

at the Indra Club. The Silver Beatles became the

Beatles and, by 1960, when they returned to England,

the band had become the talk of Liverpool. In

1962, John married Cynthia Powell and they had

a son, Julian. John and Cynthia were divorced

in 1968. Later in 1962, Richard Starkey -- or

Ringo Starr -- replaced Best as the Beatles' drummer

and the rest -- as Lennon often says sarcastically

-- is pop history.

PLAYBOY: The word is out: John Lennon and Yoko

Ono are back in the studio, recording again for

the first time since 1975, when they vanished

from public view. Let's start with you, John.

What have you been doing?

LENNON:

I've been baking bread and looking after the baby.

PLAYBOY:

With what secret projects going on in the basement?

LENNON:

That's like what everyone else who has asked me

that question over the last few years says. "But

what else have you been doing?" To which

I say, "Are you kidding?" Because bread

and babies, as every housewife knows, is a full-time

job. After I made the loaves, I felt like I had

conquered something. But as I watched the bread

being eaten, I thought, Well, Jesus, don't I get

a gold record or knighted or nothing?

PLAYBOY:

Why did you become a househusband?

LENNON:

There were many reasons. I had been under obligation

or contract from the time I was 22 until well

into my 30s. After all those years, it was all

I knew. I wasn't free. I was boxed in. My contract

was the physical manifestation of being in prison.

It was more important to face myself and face

that reality than to continue a life of rock 'n'

roll -- and to go up and down with the whims of

either your own performance or the public's opinion

of you. Rock 'n' roll was not fun anymore. I chose

not to take the standard options in my business

-- going to Vegas and singing your great hits,

if you're lucky, or going to hell, which is where

Elvis went.

ONO:

John was like an artist who is very good at drawing

circles. He sticks to that and it becomes his

label. He has a gallery to promote that. And the

next year, he will do triangles or something.

It doesn't reflect his life at all. When you continue

doing the same thing for ten years, you get a

prize for having done it.

LENNON:

You get the big prize when you get cancer and

you have been drawing circles and triangles for

ten years. I had become a craftsman and I could

have continued being a craftsman. I respect craftsmen,

but I am not interested in becoming one.

ONO:

Just to prove that you can go on dishing out things.

PLAYBOY:

You're talking about records, of course.

LENNON:

Yeah, to churn them out because I was expected

to, like so many people who put out an album every

six months because they're supposed to.

PLAYBOY:

Would you be referring to Paul McCartney?

LENNON:

Not only Paul. But I had lost the initial freedom

of the artist by becoming enslaved to the image

of what the artist is supposed to do. A lot of

artists kill themselves because of it, whether

it is through drink, like Dylan Thomas, or through

insanity, like Van Gogh, or through V.D., like

Gauguin.

PLAYBOY:

Most people would have continued to churn out

the product. How were you able to see a way out?

LENNON:

Most people don't live with Yoko Ono.

PLAYBOY:

Which means?

LENNON:

Most people don't have a companion who will tell

the truth and refuse to live with a bullshit artist,

which I am pretty good at. I can bullshit myself

and everybody around. Yoko: That's my answer.

PLAYBOY:

What did she do for you?

LENNON:

She showed me the possibility of the alternative.

"You don't have to do this." "I

don't? Really? But--but--but--but--but...."

Of course, it wasn't that simple and it didn't

sink in overnight. It took constant reinforcement.

Walking away is much harder than carrying on.

I've done both. On demand and on schedule, I had

turned out records from 1962 to 1975. Walking

away seemed like what the guys go through at 65,

when suddenly they're supposed to not exist anymore

and they're sent out of the office [knocks on

the desk three times]: "Your life is over.

Time for golf."

PLAYBOY:

Yoko, how did you feel about John's becoming a

househusband?

ONO:

When John and I would go out, people would come

up and say, "John, what are you doing?"

but they never asked about me, because, as a woman,

I wasn't supposed to be doing anything.

LENNON:

When I was cleaning the cat shit and feeding Sean,

she was sitting in rooms full of smoke with men

in three-piece suits that they couldn't button.

ONO:

I handled the business: old business -- Apple,

Maclen [the Beatles' record company and publishing

company, respectively] and new investments.

LENNON:

We had to face the business. It was either another

case of asking some daddy to come solve our business

or having one of us do it. Those lawyers were

getting a quarter of a million dollars a year

to sit around a table and eat salmon at the Plaza.

Most of them didn't seem interested in solving

the problems. Every lawyer had a lawyer. Each

Beatle had four or five people working. So we

felt we had to look after that side of the business

and get rid of it and deal with it before we could

start dealing with our own life. And the only

one of us who has the talent or the ability to

deal with it on that level is Yoko.

PLAYBOY:

Did you have experience handling business matters

of that proportion?

ONO:

I learned. The law is not a mystery to me anymore.

Politicians are not a mystery to me. I'm not scared

of all that establishment anymore. At first, my

own accountant and my own lawyer could not deal

with the fact that I was telling them what to

do.

LENNON:

There was a bit of an attitude that this is John's

wife, but surely she can't really be representing

him.

ONO:

A lawyer would send a letter to the directors,

but instead of sending it to me, he would send

it to John or send it to my lawyer. You'd be surprised

how much insult I took from them initially. There

was all this "But you don't know anything

about law; I can't talk to you." I said,

"All right, talk to me in the way I can understand

it. I am a director, too."

LENNON:

They can't stand it. But they have to stand it,

because she is who represents us. [Chuckles] They're

all male, you know, just big and fat, vodka lunch,

shouting males, like trained dogs, trained to

attack all the time. Recently, she made it possible

for us to earn a large sum of money that benefited

all of them and they fought and fought not to

let her do it, because it was her idea and she

was a woman and she was not a professional. But

she did it, and then one of the guys said to her,

"Well, Lennon does it again." But Lennon

didn't have anything to do with it.

PLAYBOY:

Why are you returning to the studio and public

life?

LENNON:

You breathe in and you breathe out. We feel like

doing it and we have something to say. Also, Yoko

and I attempted a few times to make music together,

but that was a long time ago and people still

had the idea that the Beatles were some kind of

sacred thing that shouldn't step outside its circle.

It was hard for us to work together then. We think

either people have forgotten or they have grown

up by now, so we can make a second foray into

that place where she and I are together, making

music -- simply that. It's not like I'm some wondrous,

mystic prince from the rock-'n'-roll world dabbling

in strange music with this exotic, Oriental dragon

lady, which was the picture projected by the press

before.

PLAYBOY:

Some people have accused you of playing to the

media. First you become a recluse, then you talk

selectively to the press because you have a new

album coming out.

LENNON:

That's ridiculous. People always said John and

Yoko would do anything for the publicity. In the

Newsweek article [September 29, 1980], it says

the reporter asked us, "Why did you go underground?"

Well, she never asked it that way and I didn't

go underground. I just stopped talking to the

press. It got to be pretty funny. I was calling

myself Greta Hughes or Howard Garbo through that

period. But still the gossip items never stopped.

We never stopped being in the press, but there

seemed to be more written about us when we weren't

talking to the press than when we were.

PLAYBOY:

How do you feel about all the negative press that's

been directed through the years at Yoko, your

"dragon lady," as you put it?

LENNON:

We are both sensitive people and we were hurt

a lot by it. I mean, we couldn't understand it.

When you're in love, when somebody says something

like, "How can you be with that woman?"

you say, "What do you mean? I am with this

goddess of love, the fulfillment of my whole life.

Why are you saying this? Why do you want to throw

a rock at her or punish me for being in love with

her?" Our love helped us survive it, but

some of it was pretty violent. There were a few

times when we nearly went under, but we managed

to survive and here we are. [Looks upward] Thank

you, thank you, thank you.

PLAYBOY:

But what about the charge that John Lennon is

under Yoko's spell, under her control?

LENNON:

Well, that's rubbish, you know. Nobody controls

me. I'm uncontrollable. The only one who controls

me is me, and that's just barely possible.

PLAYBOY:

Still, many people believe it.

LENNON:

Listen, if somebody's gonna impress me, whether

it be a Maharishi or a Yoko Ono, there comes a

point when the emperor has no clothes. There comes

a point when I will see. So for all you folks

out there who think that I'm having the wool pulled

over my eyes, well, that's an insult to me. Not

that you think less of Yoko, because that's your

problem. What I think of her is what counts! Because

-- fuck you, brother and sister -- you don't know

what's happening. I'm not here for you. I'm here

for me and her and the baby!

ONO:

Of course, it's a total insult to me----

LENNON:

Well, you're always insulted, my dear wife. It's

natural----

ONO:

Why should I bother to control anybody?

LENNON:

She doesn't need me.

ONO:

I have my own life, you know.

LENNON:

She doesn't need a Beatle. Who needs a Beatle?

ONO:

Do people think I'm that much of a con? John lasted

two months with the Maharishi. Two months. I must

be the biggest con in the world, because I've

been with him 13 years.

LENNON:

But people do say that.

PLAYBOY:

That's our point. Why?

LENNON:

They want to hold on to something they never had

in the first place. Anybody who claims to have

some interest in me as an individual artist or

even as part of the Beatles has absolutely misunderstood

everything I ever said if they can't see why I'm

with Yoko. And if they can't see that, they don't

see anything. They're just jacking off to -- it

could be anybody. Mick Jagger or somebody else.

Let them go jack off to Mick Jagger, OK? I don't

need it.

PLAYBOY:

He'll appreciate that.

LENNON:

I absolutely don't need it. Let them chase Wings.

Just forget about me. If that's what you want,

go after Paul or Mick. I ain't here for that.

If that's not apparent in my past, I'm saying

it in black and green, next to all the tits and

asses on page 196. Go play with the other boys.

Don't bother me. Go play with the Rolling Wings.

PLAYBOY:

Do you----

LENNON:

No, wait a minute. Let's stay with this a second;

sometimes I can't let go of it. [He is on his

feet, climbing up the refrigerator] Nobody ever

said anything about Paul's having a spell on me

or my having one on Paul! They never thought that

was abnormal in those days, two guys together,

or four guys together! Why didn't they ever say,

"How come those guys don't split up? I mean,

what's going on backstage? What is this Paul and

John business? How can they be together so long?"

We spent more time together in the early days

than John and Yoko: the four of us sleeping in

the same room, practically in the same bed, in

the same truck, living together night and day,

eating, shitting and pissing together! All right?

Doing everything together! Nobody said a damn

thing about being under a spell. Maybe they said

we were under the spell of Brian Epstein or George

Martin [the Beatles' first manager and producer,

respectively]. There's always somebody who has

to be doing something to you. You know, they're

congratulating the Stones on being together 112

years. Whoooopee! At least Charlie and Bill still

got their families. In the Eighties, they'll be

asking, "Why are those guys still together?

Can't they hack it on their own? Why do they have

to be surrounded by a gang? Is the little leader

scared somebody's gonna knife him in the back?"

That's gonna be the question. That's-a-gonna be

the question! They're gonna look back at the Beatles

and the Stones and all those guys are relics.

The days when those bands were just all men will

be on the newsreels, you know. They will be showing

pictures of the guy with lipstick wriggling his

ass and the four guys with the evil black make-up

on their eyes trying to look raunchy. That's gonna

be the joke in the future, not a couple singing

together or living and working together. It's

all right when you're 16, 17, 18 to have male

companions and idols, OK? It's tribal and it's

gang and it's fine. But when it continues and

you're still doing it when you're 40, that means

you're still 16 in the head.

PLAYBOY:

Let's start at the beginning. Tell us the story

of how the wondrous mystic prince and the exotic

Oriental dragon lady met.

LENNON:

It was in 1966 in England. I'd been told about

this "event" -- this Japanese avant-garde

artist coming from America. I was looking around

the gallery and I saw this ladder and climbed

up and got a look in this spyglass on the top

of the ladder -- you feel like a fool -- and it

just said, Yes. Now, at the time, all the avant-garde

was smash the piano with a hammer and break the

sculpture and anti-, anti-, anti-, anti-, anti.

It was all boring negative crap, you know. And

just that Yes made me stay in a gallery full of

apples and nails. There was a sign that said,

Hammer A Nail In, so I said, "Can I hammer

a nail in?" But Yoko said no, because the

show wasn't opening until the next day. But the

owner came up and whispered to her, "Let

him hammer a nail in. You know, he's a millionaire.

He might buy it." And so there was this little

conference, and finally she said, "OK, you

can hammer a nail in for five shillings."

So smartass says, "Well, I'll give you an

imaginary five shillings and hammer an imaginary

nail in." And that's when we really met.

That's when we locked eyes and she got it and

I got it and, as they say in all the interviews

we do, the rest is history.

PLAYBOY:

What happened next?

LENNON:

Of course, I was a Beatle, but things had begun

to change. In 1966, just before we met, I went

to Almeria, Spain, to make the movie "How

I Won the War." It did me a lot of good to

get away. I was there six weeks. I wrote "Strawberry

Fields" Forever" there, by the way.

It gave me time to think on my own, away from

the others. From then on, I was looking for somewhere

to go, but I didn't have the nerve to really step

out on the boat by myself and push it off. But

when I fell in love with Yoko, I knew, My God,

this is different from anything I've ever known.

This is something other. This is more than a hit

record, more than gold, more than everything.

It is indescribable.

PLAYBOY:

Were falling in love with Yoko and wanting to

leave the Beatles connected?

LENNON:

As I said, I had already begun to want to leave,

but when I met Yoko is like when you meet your

first woman. You leave the guys at the bar. You

don't go play football anymore. You don't go play

snooker or billiards. Maybe some guys do it on

Friday night or something, but once I found the

woman, the boys became of no interest whatsoever

other than being old school friends. "Those

wedding bells are breaking up that old gang of

mine." We got married three years later,

in 1969. That was the end of the boys. And it

just so happened that the boys were well known

and weren't just local guys at the bar. Everybody

got so upset over it. There was a lot of shit

thrown at us. A lot of hateful stuff.

ONO:

Even now, I just read that Paul said, "I

understand that he wants to be with her, but why

does he have to be with her all the time?"

LENNON:

Yoko, do you still have to carry that cross? That

was years ago.

ONO:

No, no, no. He said it recently. I mean, what

happened with John is like, I sort of went to

bed with this guy that I liked and suddenly the

next morning, I see these three in-laws, standing

there.

LENNON:

I've always thought there was this underlying

thing in Paul's "Get Back." When we

were in the studio recording it, every time he

sang the line "Get back to where you once

belonged," he'd look at Yoko.

PLAYBOY:

Are you kidding?

LENNON:

No. But maybe he'll say I'm paranoid. [The next

portion of the interview took place with Lennon

alone.]

PLAYBOY:

This may be the time to talk about those "in-laws,"

as Yoko put it. John, you've been asked this a

thousand times, but why is it so unthinkable that

the Beatles might get back together to make some

music?

LENNON:

Do you want to go back to high school? Why should

I go back ten years to provide an illusion for

you that I know does not exist? It cannot exist.

PLAYBOY:

Then forget the illusion. What about just to make

some great music again? Do you acknowledge that

the Beatles made great music?

LENNON:

Why should the Beatles give more? Didn't they

give everything on God's earth for ten years?

Didn't they give themselves? You're like the typical

sort of love-hate fan who says, "Thank you

for everything you did for us in the Sixties --

would you just give me another shot? Just one

more miracle?"

PLAYBOY:

We're not talking about miracles -- just good

music.

LENNON:

When Rodgers worked with Hart and then worked

with Hammerstein, do you think he should have

stayed with one instead of working with the other?

Should Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis have stayed

together because I used to like them together?

What is this game of doing things because other

people want it? The whole Beatle idea was to do

what you want, right? To take your own responsibility.

PLAYBOY:

All right, but get back to the music itself: You

don't agree that the Beatles created the best

rock 'n' roll that's been produced?

LENNON:

I don't. The Beatles, you see -- I'm too involved

in them artistically. I cannot see them objectively.

I cannot listen to them objectively. I'm dissatisfied

with every record the Beatles ever fucking made.

There ain't one of them I wouldn't remake -- including

all the Beatles records and all my individual

ones. So I cannot possibly give you an assessment

of what the Beatles are. When I was a Beatle,

I thought we were the best fucking group in the

god-damned world. And believing that is what made

us what we were -- whether we call it the best

rock-'n'-roll group or the best pop group or whatever.

But you play me those tracks today and I want

to remake every damn one of them. There's not

a single one. . . . I heard "Lucy in the

Sky with Diamonds" on the radio last night.

It's abysmal, you know. The track is just terrible.

I mean, it's great, but it wasn't made right,

know what I mean? But that's the artistic trip,

isn't it? That's why you keep going. But to get

back to your original question about the Beatles

and their music, the answer is that we did some

good stuff and we did some bad stuff.

PLAYBOY:

Many people feel that none of the songs Paul has

done alone match the songs he did as a Beatle.

Do you honestly feel that any of your songs --

on the Plastic Ono Band records -- will have the

lasting imprint of "Eleanor Rigby" or

"Strawberry Fields"?

LENNON:

"Imagine," "Love" and those

Plastic Ono Band songs stand up to any song that

was written when I was a Beatle. Now, it may take

you 20 or 30 years to appreciate that, but the

fact is, if you check those songs out, you will

see that it is as good as any fucking stuff that

was ever done.

PLAYBOY:

It seems as if you're trying to say to the world,

"We were just a good band making some good

music," while a lot of the rest of the world

is saying, "It wasn't just some good music,

it was the best."

LENNON:

Well, if it was the best, so what?

PLAYBOY:

So----

LENNON:

It can never be again! Everyone always talks about

a good thing coming to an end, as if life was

over. But I'll be 40 when this interview comes

out. Paul is 38. Elton John, Bob Dylan -- we're

all relatively young people. The game isn't over

yet. Everyone talks in terms of the last record

or the last Beatle concert -- but, God willing,

there are another 40 years of productivity to

go. I'm not judging whether "I am the Walrus"

is better or worse than "Imagine." It

is for others to judge. I am doing it. I do. I

don't stand back and judge -- I do.

PLAYBOY:

You keep saying you don't want to go back ten

years, that too much has changed. Don't you ever

feel it would be interesting -- never mind cosmic,

just interesting -- to get together, with all

your new experiences, and cross your talents?

LENNON:

Wouldn't it be interesting to take Elvis back

to his Sun Records period? I don't know. But I'm

content to listen to his Sun Records. I don't

want to dig him up out of the grave. The Beatles

don't exist and can never exist again. John Lennon,

Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Richard Starkey

could put on a concert -- but it can never be

the Beatles singing "Strawberry Fields"

or "I am the Walrus" again, because

we are not in our 20s. We cannot be that again,

nor can the people who are listening.

PLAYBOY:

But aren't you the one who is making it too important?

What if it were just nostalgic fun? A high school

reunion?

LENNON:

I never went to high school reunions. My thing

is, Out of sight, out of mind. That's my attitude

toward life. So I don't have any romanticism about

any part of my past. I think of it only inasmuch

as it gave me pleasure or helped me grow psychologically.

That is the only thing that interests me about

yesterday. I don't believe in yesterday, by the

way. You know I don't believe in yesterday. I

am only interested in what I am doing now.

PLAYBOY:

What about the people of your generation, the

ones who feel a certain kind of music -- and spirit

-- died when the Beatles broke up?

LENNON:

If they didn't understand the Beatles and the

Sixties then, what the fuck could we do for them

now? Do we have to divide the fish and the loaves

for the multitudes again? Do we have to get crucified

again? Do we have to do the walking on water again

because a whole pile of dummies didn't see it

the first time, or didn't believe it when they

saw it? You know, that's what they're asking:

"Get off the cross. I didn't understand the

first bit yet. Can you do that again?" No

way. You can never go home. It doesn't exist.

PLAYBOY:

Do you find that the clamor for a Beatles reunion

has died down?

LENNON:

Well, I heard some Beatles stuff on the radio

the other day and I heard "Green Onion"

-- no, "Glass Onion," I don't even know

my own songs! I listened to it because it was

a rare track----

PLAYBOY:

That was the one that contributed to the "Paul

McCartney is dead" uproar because of the

lyric "The walrus is Paul."

LENNON:

Yeah. That line was a joke, you know. That line

was put in partly because I was feeling guilty

because I was with Yoko, and I knew I was finally

high and dry. In a perverse way, I was sort of

saying to Paul, "Here, have this crumb, have

this illusion, have this stroke -- because I'm

leaving you." Anyway, it's a song they don't

usually play. When a radio station has a Beatles

weekend, they usually play the same ten songs

-- "A Hard Day's Night," "Help!,"

"Yesterday," "Something,"

"Let It Be" -- you know, there's all

that wealth of material, but we hear only ten

songs. So the deejay says, "I want to thank

John, Paul, George and Ringo for not getting back

together and spoiling a good thing." I thought

it was a good sign. Maybe people are catching

on.

PLAYBOY:

Aside from the millions you've been offered for

a reunion concert, how did you feel about producer

Lorne Michaels' generous offer of $3200 for appearing

together on "Saturday Night Live" a

few years ago?

LENNON:

Oh, yeah. Paul and I were together watching that

show. He was visiting us at our place in the Dakota.

We were watching it and almost went down to the

studio, just as a gag. We nearly got into a cab,

but we were actually too tired.

PLAYBOY:

How did you and Paul happen to be watching TV

together?

LENNON:

That was a period when Paul just kept turning

up at our door with a guitar. I would let him

in, but finally I said to him, "Please call

before you come over. It's not 1956 and turning

up at the door isn't the same anymore. You know,

just give me a ring." He was upset by that,

but I didn't mean it badly. I just meant that

I was taking care of a baby all day and some guy

turns up at the door. . . . But, anyway, back

on that night, he and Linda walked in and he and

I were just sitting there, watching the show,

and we went, "Ha-ha, wouldn't it be funny

if we went down?" but we didn't.

PLAYBOY:

Was that the last time you saw Paul?

LENNON:

Yes, but I didn't mean it like that.

PLAYBOY:

We're asking because there's always a lot of speculation

about whether the Fab Four are dreaded enemies

or the best of friends.

LENNON:

We're neither. I haven't seen any of the Beatles

for I don't know how much time. Somebody asked

me what I thought of Paul's last album and I made

some remark like, I thought he was depressed and

sad. But then I realized I hadn't listened to

the whole damn thing. I heard one track -- the

hit "Coming Up," which I thought was

a good piece of work. Then I heard something else

that sounded like he was depressed. But I don't

follow their work. I don't follow Wings, you know.

I don't give a shit what Wings is doing, or what

George's new album is doing, or what Ringo is

doing. I'm not interested, no more than I am in

what Elton John or Bob Dylan is doing. It's not

callousness, it's just that I'm too busy living

my own life to be following what other people

are doing, whether they're the Beatles or guys

I went to college with or people I had intense

relationships with before I met the Beatles.

PLAYBOY:

Besides "Coming Up," what do you think

of Paul's work since he left the Beatles?

LENNON:

I kind of admire the way Paul started back from

scratch, forming a new band and playing in small

dance halls, because that's what he wanted to

do with the Beatles -- he wanted us to go back

to the dance halls and experience that again.

But I didn't. . . . That was one of the problems,

in a way, that he wanted to relive it all or something

-- I don't know what it was. . . . But I kind

of admire the way he got off his pedestal -- now

he's back on it again, but I mean, he did what

he wanted to do. That's fine, but it's just not

what I wanted to do.

PLAYBOY:

What about the music?

LENNON:

"The Long and Winding Road" was the

last gasp from him. Although I really haven't

listened.

PLAYBOY:

You say you haven't listened to Paul's work and

haven't really talked to him since that night

in your apartment----

LENNON:

Really talked to him, no, that's the operative

word. I haven't really talked to him in ten years.

Because I haven't spent time with him. I've been

doing other things and so has he. You know, he's

got 25 kids and about 20,000,000 records out --

how can he spend time talking? He's always working.

PLAYBOY:

Then let's talk about the work you did together.

Generally speaking, what did each of you contribute

to the Lennon-McCartney songwriting team?

LENNON:

Well, you could say that he provided a lightness,

an optimism, while I would always go for the sadness,

the discords, a certain bluesy edge. There was

a period when I thought I didn't write melodies,

that Paul wrote those and I just wrote straight,

shouting rock 'n' roll. But, of course, when I

think of some of my own songs -- "In My Life"

-- or some of the early stuff -- "This Boy"

-- I was writing melody with the best of them.

Paul had a lot of training, could play a lot of

instruments. He'd say, "Well, why don't you

change that there? You've done that note 50 times

in the song." You know, I'll grab a note

and ram it home. Then again, I'd be the one to

figure out where to go with a song -- a story

that Paul would start. In a lot of the songs,

my stuff is the "middle eight," the

bridge.

PLAYBOY:

For example?

LENNON:

Take "Michelle." Paul and I were staying

somewhere, and he walked in and hummed the first

few bars, with the words, you know [sings verse

of "Michelle"], and he says, "Where

do I go from here?" I'd been listening to

blues singer Nina Simone, who did something like

"I love you!" in one of her songs and

that made me think of the middle eight for "Michelle"

[sings]: "I love you, I love you, I l-o-ove

you . . . ."

PLAYBOY:

What was the difference in terms of lyrics?

LENNON:

I always had an easier time with lyrics, though

Paul is quite a capable lyricist who doesn't think

he is. So he doesn't go for it. Rather than face

the problem, he would avoid it. "Hey, Jude"

is a damn good set of lyrics. I made no contribution

to the lyrics there. And a couple of lines he

has come up with show indications of a good lyricist.

But he just hasn't taken it anywhere. Still, in

the early days, we didn't care about lyrics as

long as the song had some vague theme -- she loves

you, he loves him, they all love each other. It

was the hook, line and sound we were going for.

That's still my attitude, but I can't leave lyrics

alone. I have to make them make sense apart from

the songs.

PLAYBOY:

What's an example of a lyric you and Paul worked

on together?

LENNON:

In "We Can Work It Out," Paul did the

first half, I did the middle eight. But you've

got Paul writing, "We can work it out/We

can work it out" -- real optimistic, y' know,

and me, impatient: "Life is very short and

there's no time/For fussing and fighting, my friend...."

PLAYBOY:

Paul tells the story and John philosophizes.

LENNON:

Sure. Well, I was always like that, you know.

I was like that before the Beatles and after the

Beatles. I always asked why people did things

and why society was like it was. I didn't just

accept it for what it was apparently doing. I

always looked below the surface.

PLAYBOY:

When you talk about working together on a single

lyric like "We Can Work It Out," it

suggests that you and Paul worked a lot more closely

than you've admitted in the past. Haven't you

said that you wrote most of your songs separately,

despite putting both of your names on them?

LENNON:

Yeah, I was lying. [Laughs] It was when I felt

resentful, so I felt that we did everything apart.

But, actually, a lot of the songs we did eyeball

to eyeball.

PLAYBOY:

But many of them were done apart, weren't they?

LENNON:

Yeah. "Sgt. Pepper" was Paul's idea,

and I remember he worked on it a lot and suddenly

called me to go into the studio, said it was time

to write some songs. On "Pepper," under

the pressure of only ten days, I managed to come

up with "Lucy in the Sky" and "Day

in the Life." We weren't communicating enough,

you see. And later on, that's why I got resentful

about all that stuff. But now I understand that

it was just the same competitive game going on.

PLAYBOY:

But the competitive game was good for you, wasn't

it?

LENNON:

In the early days. We'd make a record in 12 hours

or something; they would want a single every three

months and we'd have to write it in a hotel room

or in a van. So the cooperation was functional

as well as musical.

PLAYBOY:

Don't you think that cooperation, that magic between

you, is something you've missed in your work since?

LENNON:

I never actually felt a loss. I don't want it

to sound negative, like I didn't need Paul, because

when he was there, obviously, it worked. But I

can't -- it's easier to say what I gave to him

than what he gave to me. And he'd say the same.

PLAYBOY:

Just a quick aside, but while we're on the subject

of lyrics and your resentment of Paul, what made

you write "How Do You Sleep?," which

contains lyrics such as "Those freaks was

right when they said you was dead" and "The

only thing you done was yesterday/And since you've

gone, you're just another day"?

LENNON:

[Smiles] You know, I wasn't really feeling that

vicious at the time. But I was using my resentment

toward Paul to create a song, let's put it that

way. He saw that it pointedly refers to him, and

people kept hounding him about it. But, you know,

there were a few digs on his album before mine.

He's so obscure other people didn't notice them,

but I heard them. I thought, Well, I'm not obscure,

I just get right down to the nitty-gritty. So

he'd done it his way and I did it mine. But as

to the line you quoted, yeah, I think Paul died

creatively, in a way.

PLAYBOY:

That's what we were getting at: You say that what

you've done since the Beatles stands up well,

but isn't it possible that with all of you, it's

been a case of the creative whole being greater

than the parts?

LENNON:

I don't know whether this will gel for you: When

the Beatles played in America for the first time,

they played pure craftsmanship. Meaning they were

already old hands. The jism had gone out of the

performances a long time ago. In the same respect,

the songwriting creativity had left Paul and me

in the mid-Sixties. When we wrote together in

the early days, it was like the beginning of a

relationship. Lots of energy. In the "Sgt.

Pepper"- "Abbey Road" period, the

relationship had matured. Maybe had we gone on

together, more interesting things would have come,

but it couldn't have been the same.

PLAYBOY:

Let's move on to Ringo. What's your opinion of

him musically?

LENNON:

Ringo was a star in his own right in Liverpool

before we even met. He was a professional drummer

who sang and performed and had Ringo Star-time

and he was in one of the top groups in Britain

but especially in Liverpool before we even had

a drummer. So Ringo's talent would have come out

one way or the other as something or other. I

don't know what he would have ended up as, but

whatever that spark is in Ringo that we all know

but can't put our finger on -- whether it is acting,

drumming or singing I don't know -- there is something

in him that is projectable and he would have surfaced

with or without the Beatles. Ringo is a damn good

drummer. He is not technically good, but I think

Ringo's drumming is underrated the same way Paul's

bass playing is underrated. Paul was one of the

most innovative bass players ever. And half the

stuff that is going on now is directly ripped

off from his Beatles period. He is an egomaniac

about everything else about himself, but his bass

playing he was always a bit coy about. I think

Paul and Ringo stand up with any of the rock musicians.

Not technically great -- none of us are technical

musicians. None of us could read music. None of

us can write it. But as pure musicians, as inspired

humans to make the noise, they are as good as

anybody.

PLAYBOY:

How about George's solo music?

LENNON:

I think "All Things Must Pass" was all

right. It just went on too long.

PLAYBOY:

How did you feel about the lawsuit George lost

that claimed the music to "My Sweet Lord"

is a rip-off of the Shirelles' hit "He's

So Fine?"

LENNON:

Well, he walked right into it. He knew what he

was doing.

PLAYBOY:

Are you saying he consciously plagiarized the

song?

LENNON:

He must have known, you know. He's smarter than

that. It's irrelevant, actually -- only on a monetary

level does it matter. He could have changed a

couple of bars in that song and nobody could ever

have touched him, but he just let it go and paid

the price. Maybe he thought God would just sort

of let him off. [At presstime, the court has found

Harrison guilty of "subconscious" plagiarism

but has not yet ruled on damages.]

PLAYBOY:

You actually haven't mentioned George much in

this interview.

LENNON:

Well, I was hurt by George's book, "I, Me,

Mine" -- so this message will go to him.

He put a book out privately on his life that,

by glaring omission, says that my influence on

his life is absolutely zilch and nil. In his book,

which is purportedly this clarity of vision of

his influence on each song he wrote, he remembers

every two-bit sax player or guitarist he met in

subsequent years. I'm not in the book.

PLAYBOY:

Why?

LENNON:

Because George's relationship with me was one

of young follower and older guy. He's three or

four years younger than me. It's a love- hate

relationship and I think George still bears resentment

toward me for being a daddy who left home. He

would not agree with this, but that's my feeling

about it. I was just hurt. I was just left out,

as if I didn't exist. I don't want to be that

egomaniacal, but he was like a disciple of mine

when we started. I was already an art student

when Paul and George were still in grammar school

[equivalent to high school in the U.S.]. There

is a vast difference between being in high school

and being in college and I was already in college

and already had sexual relationships, already

drank and did a lot of things like that. When

George was a kid, he used to follow me and my

first girlfriend, Cynthia -- who became my wife

-- around. We'd come out of art school and he'd

be hovering around like those kids at the gate

of the Dakota now. I remember the day he called

to ask for help on "Taxman," one of

his bigger songs. I threw in a few one-liners

to help the song along, because that's what he

asked for. He came to me because he couldn't go

to Paul, because Paul wouldn't have helped him

at that period. I didn't want to do it. I thought,

Oh, no, don't tell me I have to work on George's

stuff. It's enough doing my own and Paul's. But

because I loved him and I didn't want to hurt

him when he called me that afternoon and said,

"Will you help me with this song?" I

just sort of bit my tongue and said OK. It had

been John and Paul so long, he'd been left out

because he hadn't been a songwriter up until then.

As a singer, we allowed him only one track on

each album. If you listen to the Beatles' first

albums, the English versions, he gets a single

track. The songs he and Ringo sang at first were

the songs that used to be part of my repertoire

in the dance halls. I used to pick songs for them

from my repertoire -- the easier ones to sing.

So I am slightly resentful of George's book. But

don't get me wrong. I still love those guys. The

Beatles are over, but John, Paul, George and Ringo

go on.

PLAYBOY:

Didn't all four Beatles work on a song you wrote

for Ringo in 1973?

LENNON:

"I'm the Greatest." It was the Muhammad

Ali line, of course. It was perfect for Ringo

to sing. If I said, "I'm the greatest,"

they'd all take it so seriously. No one would

get upset with Ringo singing it.

PLAYBOY:

Did you enjoy playing with George and Ringo again?

LENNON:

Yeah, except when George and Billy Preston started

saying, "Let's form a group. Let's form a

group." I was embarrassed when George kept

asking me. He was just enjoying the session and

the spirit was very good, but I was with Yoko,

you know. We took time out from what we were doing.

The very fact that they would imagine I would

form a male group without Yoko! It was still in

their minds. . . .

PLAYBOY:

Just to finish your favorite subject, what about

the suggestion that the four of you put aside

your personal feelings and regroup to give a mammoth

concert for charity, some sort of giant benefit?

LENNON:

I don't want to have anything to do with benefits.

I have been benefited to death.

PLAYBOY:

Why?

LENNON:

Because they're always rip-offs. I haven't performed

for personal gain since 1966, when the Beatles

last performed. Every concert since then, Yoko

and I did for specific charities, except for a

Toronto thing that was a rock-'n'-roll revival.

Every one of them was a mess or a rip-off. So

now we give money to who we want. You've heard

of tithing?

PLAYBOY:

That's when you give away a fixed percentage of

your income.

LENNON:

Right. I am just going to do it privately. I am

not going to get locked into that business of

saving the world on stage. The show is always

a mess and the artist always comes off badly.

PLAYBOY:

What about the Bangladesh concert, in which George

and other people such as Dylan performed?

LENNON:

Bangladesh was caca.

PLAYBOY:

You mean because of all the questions that were

raised about where the money went?

LENNON:

Yeah, right. I can't even talk about it, because

it's still a problem. You'll have to check with

Mother [Yoko], because she knows the ins and outs

of it, I don't. But it's all a rip-off. So forget

about it. All of you who are reading this, don't

bother sending me all that garbage about, "Just

come and save the Indians, come and save the blacks,

come and save the war veterans," Anybody

I want to save will be helped through our tithing,

which is ten percent of whatever we earn.

PLAYBOY:

But that doesn't compare with what one promoter,

Sid Bernstein, said you could raise by giving

a world-wide televised concert -- playing separately,

as individuals, or together, as the Beatles. He

estimated you could raise over $200,000,000 in

one day.

LENNON:

That was a commercial for Sid Bernstein written

with Jewish schmaltz and showbiz and tears, dropping

on one knee. It was Al Jolson. OK. So I don't

buy that. OK.

PLAYBOY:

But the fact is, $200,000,000 to a poverty-stricken

country in South America----

LENNON:

Where do people get off saying the Beatles should

give $200,000,000 to South America? You know,

America has poured billions into places like that.

It doesn't mean a damn thing. After they've eaten

that meal, then what? It lasts for only a day.

After the $200,000,000 is gone, then what? It

goes round and round in circles. You can pour

money in forever. After Peru, then Harlem, then

Britain. There is no one concert. We would have

to dedicate the rest of our lives to one world

concert tour, and I'm not ready for it. Not in

this lifetime, anyway. [Ono rejoins the conversation.]

PLAYBOY:

On the subject of your own wealth, the New York

Post recently said you admitted to being worth

over $150,000,000 and----

LENNON:

We never admitted anything.

PLAYBOY:

The Post said you had.

LENNON:

What the Post says -- OK, so we are rich; so what?

PLAYBOY:

The question is, How does that jibe with your

political philosophies? You're supposed to be

socialists, aren't you?

LENNON:

In England, there are only two things to be, basically:

You are either for the labor movement or for the

capitalist movement. Either you become a right-wing

Archie Bunker if you are in the class I am in,

or you become an instinctive socialist, which

I was. That meant I think people should get their

false teeth and their health looked after, all

the rest of it. But apart from that, I worked

for money and I wanted to be rich. So what the

hell -- if that's a paradox, then I'm a socialist.

But I am not anything. What I used to be is guilty

about money. That's why I lost it, either by giving

it away or by allowing myself to be screwed by

so-called managers.

PLAYBOY:

Whatever your politics, you've played the capitalist

game very well, parlaying your Beatles royalties

into real estate, livestock----

ONO:

There is no denying that we are still living in

the capitalist world. I think that in order to

survive and to change the world, you have to take

care of yourself first. You have to survive yourself.

I used to say to myself, I am the only socialist

living here. [Laughs] I don't have a penny. It

is all John's, so I'm clean. But I was using his

money and I had to face that hypocrisy. I used

to think that money was obscene, that the artists

didn't have to think about money. But to change

society, there are two ways to go: through violence

or the power of money within the system. A lot

of people in the Sixties went underground and

were involved in bombings and other violence.

But that is not the way, definitely not for me.

So to change the system -- even if you are going

to become a mayor or something -- you need money.

PLAYBOY:

To what extent do you play the game without getting

caught up in it -- money for the sake of money,

in other words?

ONO:

There is a limit. It would probably be parallel

to our level of security. Do you know what I mean?

I mean the emotional-security level as well.

PLAYBOY:

Has it reached that level yet?

ONO:

No, not yet. I don't know. It might have.

PLAYBOY:

You mean with $150,000,000? Is that an accurate

estimate?

ONO:

I don't know what we have. It becomes so complex

that you need to have ten accountants working

for two years to find out what you have. But let's

say that we feel more comfortable now.

PLAYBOY:

How have you chosen to invest your money?

ONO:

To make money, you have to spend money. But if

you are going to make money, you have to make

it with love. I love Egyptian art. I make sure

to get all the Egyptian things, not for their

value but for their magic power. Each piece has

a certain magic power. Also with houses. I just

buy ones we love, not the ones that people say

are good investments.

PLAYBOY:

The papers have made it sound like you are buying

up the Atlantic Seaboard.

ONO:

If you saw the houses, you would understand. They

have become a good investment, but they are not

an investment unless you sell them. We don't intend

to sell. Each house is like a historic landmark

and they're very beautiful.

PLAYBOY:

Do you actually use all the properties?

ONO:

Most people have the park to go to and run in

-- the park is a huge place -- but John and I

were never able to go to the park together. So

we have to create our own parks, you know.

PLAYBOY:

We heard that you own $60,000,000 worth of dairy

cows. Can that be true?

ONO:

I don't know. I'm not a calculator. I'm not going

by figures. I'm going by excellence of things.

LENNON:

Sean and I were away for a weekend and Yoko came

over to sell this cow and I was joking about it.

We hadn't seen her for days; she spent all her

time on it. But then I read the paper that said

she sold it for a quarter of a million dollars.

Only Yoko could sell a cow for that much. [Laughter]

PLAYBOY:

For an artist, your business sense seems remarkable.

ONO:

I was doing it just as a chess game. I love chess.

I do everything like it's a chess game. Not on

a Monopoly level -- that's a bit more realistic.

Chess is more conceptual.

PLAYBOY:

John, do you really need all those houses around

the country?

LENNON:

They're good business.

PLAYBOY:

Why does anyone need $150,000,000? Couldn't you

be perfectly content with $100,000,000? Or $1,000,000?

LENNON:

What would you suggest I do? Give everything away

and walk the streets? The Buddhist says, "Get

rid of the possessions of the mind." Walking

away from all the money would not accomplish that.

It's like the Beatles. I couldn't walk away from

the Beatles. That's one possession that's still

tagging along, right? If I walk away from one

house or 400 houses, I'm not gonna escape it.

PLAYBOY:

How do you escape it?

LENNON:

It takes time to get rid of all this garbage that

I've been carrying around that was influencing

the way I thought and the way I lived. It had

a lot to do with Yoko, showing me that I was still

possessed. I left physically when I fell in love

with Yoko, but mentally it took the last ten years

of struggling. I learned everything from her.

PLAYBOY:

You make it sound like a teacher-pupil relationship.

LENNON:

It is a teacher-pupil relationship. That's what

people don't understand. She's the teacher and

I'm the pupil. I'm the famous one, the one who's

supposed to know everything, but she's my teacher.

She's taught me everything I fucking know. She

was there when I was nowhere, when I was the nowhere

man. She's my Don Juan [a reference to Carlos

Castaneda's Yaqui Indian teacher]. That's what

people don't understand. I'm married to fucking

Don Juan, that's the hardship of it. Don Juan

doesn't have to laugh; Don Juan doesn't have to

be charming; Don Juan just is. And what goes on

around Don Juan is irrelevant to Don Juan.

PLAYBOY:

Yoko, how do you feel about being John's teacher?

ONO:

Well, he had a lot of experience before he met

me, the kind of experience I never had, so I learned

a lot from him, too. It's both ways. Maybe it's

that I have strength, a feminine strength. Because

women develop it -- in a relationship, I think

women really have the inner wisdom and they're

carrying that while men have sort of the wisdom

to cope with society, since they created it. Men

never developed the inner wisdom; they didn't

have time. So most men do rely on women's inner

wisdom, whether they express that or not.

PLAYBOY:

Is Yoko John's guru?

LENNON:

No, a Don Juan doesn't have a following. A Don

Juan isn't in the newspaper and doesn't have disciples

and doesn't proselytize.

PLAYBOY:

How has she taught you?

LENNON:

When Don Juan said -- when Don Ono said, "Get

out! Because you're not getting it," well,

it was like being sent into the desert. And the

reason she wouldn't let me back in was because

I wasn't ready to come back in. I had to settle

things within myself. When I was ready to come

back in, she let me back in. And that's what I'm

living with.

PLAYBOY:

You're talking about your separation.

LENNON:

Yes. We were separated in the early Seventies.

She kicked me out. Suddenly, I was on a raft alone

in the middle of the universe.

PLAYBOY:

What happened?

LENNON:

Well, at first, I thought, Whoopee, whoopee! You

know, bachelor life! Whoopee! And then I woke

up one day and I thought, What is this? I want

to go home! But she wouldn't let me come home.

That's why it was 18 months apart instead of six

months. We were talking all the time on the phone

and I would say, "I don't like this, I'm

getting in trouble and I'd like to come home,

please." And she would say, "You're

not ready to come home." So what do you say?

OK, back to the bottle.

PLAYBOY:

What did she mean, you weren't ready?

LENNON:

She has her ways. Whether they be mystical or

practical. When she said it's not ready, it ain't

ready.

PLAYBOY:

Back to the bottle?

LENNON:

I was just trying to hide what I felt in the bottle.

I was just insane. It was the lost weekend that

lasted 18 months. I've never drunk so much in

my life. I tried to drown myself in the bottle

and I was with the heaviest drinkers in the business.

PLAYBOY: Such as?

LENNON:

Such as Harry Nilsson, Bobby Keyes, Keith Moon.

We couldn't pull ourselves out. We were trying

to kill ourselves. I think Harry might still be

trying, poor bugger -- God bless you, Harry, wherever

you are -- but, Jesus, you know, I had to get

away from that, because somebody was going to

die. Well, Keith did. It was like, who's going

to die first? Unfortunately, Keith was the one.

PLAYBOY:

Why the self-destruction?

LENNON:

For me, it was because of being apart. I couldn't

stand it. They had their own reasons, and it was,

Let's all drown ourselves together. From where

I was sitting, it looked like that. Let's kill

ourselves but do it like Errol Flynn, you know,

the macho, male way. It's embarrassing for me

to think about that period, because I made a big

fool of myself -- but maybe it was a good lesson

for me. I wrote "Nobody Loves You When You're

Down and Out" during that time. That's how

I felt. It exactly expresses the whole period.

For some reason, I always imagined Sinatra singing

that one. I don't know why. It's kind of a Sinatraesque

song, really. He would do a perfect job with it.

Are you listening, Frank? You need a song that

isn't a piece of nothing. Here's the one for you,

the horn arrangement and everything's made for

you. But don't ask me to produce it.

PLAYBOY:

That must have been the time the papers came out

with reports about Lennon running around town

with a Tampax on his head.

LENNON:

The stories were all so exaggerated, but... We

were all in a restaurant, drinking, not eating,

as usual at those gatherings, and I happened to

go take a pee and there was a brand-new fresh

Kotex, not Tampax, on the toilet. You know the

old trick where you put a penny on your forehead

and it sticks? I was a little high and I just

picked it up and slapped it on and it stayed,

you see. I walked out of the bathroom and I had

a Kotex on my head. Big deal. Everybody went "Ha-ha-ha"

and it fell off, but the press blew it up.

PLAYBOY:

Why did you kick John out, Yoko?

ONO:

There were many things. I'm what I call a "moving

on" kind of girl; there's a song on our new

album about it. Rather than deal with problems

in relationships, I've always moved on. That's

why I'm one of the very few survivors as a woman,

you know. Women tend to be more into men usually,

but I wasn't...

LENNON:

Yoko looks upon men as assistants... Of varying

degrees of intimacy, but basically assistants.

And this one's going to take a pee. [He exits]

ONO:

I have no comment on that. But when I met John,

women to him were basically people around who

were serving him. He had to open himself up and

face me -- and I had to see what he was going

through. But... I though I had to move on again,

because I was suffering being with John.

PLAYBOY:

Why?

ONO:

The pressure from the public, being the one who

broke up the Beatles and who made it impossible

for them to get back together. My artwork suffered,

too. I thought I wanted to be free from being

Mrs. Lennon, so I thought it would be a good idea

for him to go to L.A. and leave me alone for a

while. I had put up with it for many years. Even

early on, when John was a Beatle, we stayed in

a room and John and I were in bed and the door

was closed and all that, but we didn't lock the

door and one of the Beatle assistants just walked

in and talked to him as if I weren't there. It

was mind-blowing. I was invisible. The people

around John saw me as a terrible threat. I mean,

I heard there were plans to kill me. Not the Beatles

but the people around them.

PLAYBOY:

How did that news affect you?

ONO:

The society doesn't understand that the woman

can be castrated, too. I felt castrated. Before,

I was doing all right, thank you. My work might

not have been selling much, I might have been

poorer, but I had my pride. But the most humiliating

thing is to be looked at as a parasite. [Lennon

rejoins the conversation.]

LENNON:

When Yoko and I started doing stuff together,

we would hold press conferences and announce our

whatevers -- we're going to wear bags or whatever.

And before this one press conference, one Beatle

assistant in the upper echelon of Beatle assistants

leaned over to Yoko and said, "You know,

you don't have to work. You've got enough money,

now that you're Mrs. Lennon." And when she

complained to me about it, I couldn't understand

what she was talking about. "But this guy,"

I'd say, "He's just good old Charley, or

whatever. He's been with us 20 years...."

The same kind of thing happened in the studio.

She would say to an engineer, "I'd like a

little more treble, a little more bass,"

or "There's too much of whatever you're putting

on," and they'd look at me and say, "What

did you say, John?" Those days I didn't even

notice it myself. Now I know what she's talking

about. In Japan, when I ask for a cup of tea in

Japanese, they look at Yoko and ask, "He

wants a cup of tea?" in Japanese.

ONO:

So a good few years of that kind of thing emasculates

you. I had always been more macho than most guys

I was with, in a sense. I had always been the

breadwinner, because I always wanted to have the

freedom and the control. Suddenly, I'm with somebody

I can't possibly compete with on a level of earnings.

Finally, I couldn't take it -- or I decided not

to take it any longer. I would have had the same

difficulty even if I hadn't gotten involved with,

ah----

LENNON:

John -- John is the name.

ONO:

With John. But John wasn't just John. He was also

his group and the people around them. When I say

John, it's not just John----

LENNON:

That's John. J-O-H-N. From Johan, I believe.

PLAYBOY:

So you made him leave?

ONO:

Yes.

LENNON:

She don't suffer fools gladly, even if she's married

to him.

PLAYBOY:

How did you finally get back together?

ONO:

It slowly started to dawn on me that John was

not the trouble at all. John was a fine person.

It was society that had become too much. We laugh

about it now, but we started dating again. I wanted

to be sure. I'm thankful to John's intelligence----

LENNON:

Now, get that, editors -- you got that word?

ONO:

That he was intelligent enough to know this was

the only way that we could save our marriage,

not because we didn't love each other but because

it was getting too much for me. Nothing would

have changed if I had come back as Mrs. Lennon

again.

PLAYBOY:

What did change?

ONO:

It was good for me to do the business and regain

my pride about what I could do. And it was good

to know what he needed, the role reversal that

was so good for him.

LENNON:

And we learned that it's better for the family

if we are both working for the family, she doing

the business and me playing mother and wife. We

reordered our priorities. The number-one priority

is her and the family. Everything else revolves

around that.

ONO:

It's a hard realization. These days, the society

prefers single people. The encouragements are

to divorce or separate or be single or gay --

whatever. Corporations want singles -- they work

harder if they don't have family ties. They don't

have to worry about being home in the evenings

or on the weekends. There's not much room for

emotions about family or personal relationships.

You know, the whole thing they say to women approaching

30 that if you don't have a baby in the next few

years, you're going to be in trouble, you'll never

be a mother, so you'll never be fulfilled in that

way and----

LENNON:

Only Yoko was 73 when she had Sean. [Laughter]

ONO:

So instead of the society discouraging children,

since they are important for society, it should

encourage them. It's the responsibility of everybody.

But it is hard. A woman has to deny what she has,

her womb, if she wants to make it. It seems that

only the privileged classes can have families.

Nowadays, maybe it's only the McCartneys and the

Lennons or something.

LENNON:

Everybody else becomes a worker-consumer.

ONO:

And then Big Brother will decide -- I hate to

use the term Big Brother...

LENNON:

Too late. They've got it on tape. [Laughs]

ONO:

But, finally, the society----

LENNON:

Big Sister -- wait till she comes!

ONO:

The society will do away with the roles of men

and women. Babies will be born in test tubes and

incubators...

LENNON:

Then it's Aldous Huxley.

ONO:

But we don't have to go that way. We don't have

to deny any of our organs, you know.

LENNON:

Some of my best friends are organs----

ONO:

The new album----

LENNON:

Back to the album, very good----

ONO:

The album fights these things. The messages are

sort of old-fashioned -- family, relationships,

children.

PLAYBOY:

The album obviously reflects your new priorities.

How have things gone for you since you made that

decision?

LENNON:

We got back together, decided this was our life,

that having a baby was important to us and that

anything else was subsidiary to that. We worked

hard for that child. We went through all hell

trying to have a baby, through many miscarriages

and other problems. He is what they call a love

child in truth. Doctors told us we could never

have a child. We almost gave up. "Well, that's

it, then, we can't have one. . . ." We were

told something was wrong with my sperm, that I

abused myself so much in my youth that there was

no chance. Yoko was 43, and so they said, no way.

She has had too many miscarriages and when she

was a young girl, there were no pills, so there

were lots of abortions and miscarriages; her stomach

must be like Kew Gardens in London. No way. But

this Chinese acupuncturist in San Francisco said,

"You behave yourself. No drugs, eat well,

no drink. You have child in 18 months." And

we said, "But the English doctors said. .

. ." He said, "Forget what they said.

You have child." We had Sean and sent the

acupuncturist a Polaroid of him just before he

died, God rest his soul.

PLAYBOY:

Were there any problems because of Yoko's age?

LENNON:

Not because of her age but because of a screw-up

in the hospital and the fucking price of fame.

Somebody had made a transfusion of the wrong blood

type into Yoko. I was there when it happened,

and she starts to go rigid, and then shake, from

the pain and the trauma. I run up to this nurse

and say, "Go get the doctor!" I'm holding

on tight to Yoko while this guy gets to the hospital

room. He walks in, hardly notices that Yoko is

going through fucking convulsions, goes straight

for me, smiles, shakes my hand and says, "I've

always wanted to meet you, Mr. Lennon, I always

enjoyed your music." I start screaming: "My

wife's dying and you wanna talk about my music!"

Christ!

PLAYBOY:

Now that Sean is almost five, is he conscious

of the fact that his father was a Beatle or have

you protected him from your fame?

LENNON:

I haven't said anything. Beatles were never mentioned

to him. There was no reason to mention it; we

never played Beatle records around the house,

unlike the story that went around that I was sitting

in the kitchen for the past five years, playing

Beatle records and reliving my past like some

kind of Howard Hughes. He did see "Yellow

Submarine" at a friend's, so I had to explain

what a cartoon of me was doing in a movie.

PLAYBOY:

Does he have an awareness of the Beatles?

LENNON:

He doesn't differentiate between the Beatles and

Daddy and Mommy. He thinks Yoko was a Beatle,