1980

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by

Jonathan Cott

December 5, 1980

Published January 22, 1981

Two

Other Rolling Stone Interviews

With John Lennon

1975

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Pete Hamill

1968

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Jonathan Cott

"Welcome

to the inner sanctum!" says John Lennon,

greeting me with high-spirited, mock ceremoniousness

in Yoko Ono's beautiful cloud-ceilinged office

in their Dakota apartment. It's Friday evening,

December 5, and Yoko has been telling me how their

collaborative new album, Double Fantasy, came

about: Last spring, John and their son, Sean,

were vacationing in Bermuda while Yoko stayed

home "sorting out business," as she

puts it. She and John spoke on the phone every

day and sang each other the songs they had composed

in between calls.

"I

was at a dance club one night in Bermuda,"

John interrupts as he sits down on a couch and

Yoko gets up to bring coffee. "Upstairs,

they were playing disco, and downstairs, I suddenly

heard 'Rock Lobster' by the B-52's for the first

time. Do you know it? It sounds just like Yoko's

music, so I said to meself, 'It's time to get

out the old axe and wake the wife up!' We wrote

about twenty-five songs during those three weeks,

and we've recorded enough for another album."

"I've

been playing side two of Double Fantasy over and

over," I say, getting ready to ply him with

a question. John looks at me with a time and interview-stopping

smile. "How are you?" he asks. "It's

been like a reunion for us these last few weeks.

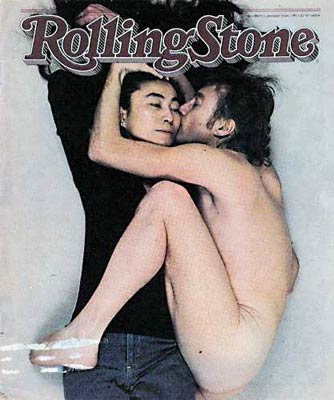

We've seen Ethan Russell, who's doing a videotape

of a couple of the new songs, and Annie Leibovitz

was here. She took my first Rolling Stone cover

photo. It's been fun seeing everyone we used to

know and doing it all again - we've all survived.

When did we first meet?"

"I

met you and Yoko on September 17, 1968,"

I say, remembering the first of our several meetings.

I was just a lucky guy, at the right place at

the right time. John had decided to become more

"public" and to demystify his Beatles

persona. He and Yoko, whom he'd met in November

1966, were preparing for the Amsterdam and Montreal

bed-ins for peace and were soon to release Two

Virgins, the first of their experimental record

collaborations. The album cover - the infamous

frontal nude portrait of them - was to grace the

pages of Rolling Stone's first anniversary issue.

John had just discovered the then-impoverished,

San Francisco-based magazine, and he'd agreed

to give Rolling Stone the first of his "coming-out"

interviews. As "European editor," I

was asked to visit John and Yoko and to take along

a photographer (Ethan Russell, who later took

the photos for the Let It Be book that accompanied

the album). So, nervous and excited, we met John

and Yoko at their temporary basement flat in London.

First

impressions are usually the most accurate, and

John was graceful, gracious, charming, exuberant,

direct, witty and playful; I remember noticing

how he wrote little reminders to himself in the

wonderfully absorbed way that a child paints the

sun. He was due at a recording session in a half-hour

to work on the White Album, so we agreed to meet

the next day to do the interview, after which

John and Yoko invited Ethan and me to attend the

session for "Back in the U.S.S.R." at

Abbey Road Studios. Only a performance of Shakespeare

at the Globe Theatre might have made me feel as

ecstatic and fortunate as I did at that moment.

Every

new encounter with John brought a new perspective.

Once, I ran into John and Yoko in 1971. A friend

and I had gone to see Carnal Knowledge, and afterward

we bumped into the Lennons in the lobby. Accompanied

by Jerry Rubin and a friend of his, they invited

us to drive down with them to Ratner's delicatessen

in the East Village for blintzes, whereupon a

beatific, long-haired young man approached our

table and wordlessly handed John a card inscribed

with a pithy saying of the inscrutable Meher Baba.

Rubin drew a swastika on the back of the card,

got up and gave it back to the man. When he returned,

John admonished him gently, saying that that wasn't

the way to change someone's consciousness. Acerbic

and skeptical as he could often be, John Lennon

never lost his sense of compassion.

Almost

ten years later, I am again talking to John, and

he is as gracious and witty as the first time

I met him. "I guess I should describe to

the readers what you're wearing, John," I

say. "Let me help you out," he offers,

then intones wryly: "You can see the glasses

he's wearing. They're normal plastic blue-frame

glasses. Nothing like the famous wire-rimmed Lennon

glasses that he stopped using in 1973. He's wearing

needle-cord pants, the same black cowboy boots

he'd had made in Nudie's in 1973, a Calvin Klein

sweater and a torn Mick Jagger T-shirt that he

got when the Stones toured in 1970 or so. And

around his neck is a small, three-part diamond

heart necklace that he bought as a make-up present

after an argument with Yoko many years ago and

that she later gave back to him in a kind of ritual.

Will that do?

"I

know you've got a Monday deadline," he adds,"

he adds, "but Yoko and I have to go to the

Record Plant now to remix a few of Yoko's songs

for a possible disco record. So why don't you

come along and we'll talk in the studio."

"You're

not putting any of your songs on this record?"

I ask as we get into the waiting car. "No,

because I don't make that stuff." He laughs

and we drive off. "I've heard that in England

some people are appreciating Yoko's songs on the

new album and are asking why I was doing that

'straight old Beatles stuff,' and I didn't know

about punk and what's going on - 'You were great

then; "Walrus" was hip, but this isn't

hip, John!' I'm really pleased for Yoko. She deserves

the praise. It's been a long haul. I'd love her

to have the A side of a hit record and me the

B side. I'd settle for it any day."

"It's

interesting," I say, "that no rock &

roll star I can think of has made a record with

his wife or whomever and given her fifty percent

of the disc."

"It's

the first time we've done it this way," John

says. "It's a dialogue, and we have resurrected

ourselves, in a way, as John and Yoko - not as

John ex-Beatle and Yoko and the Plastic Ono Band.

It's just the two of us, and our position was

that, if the record didn't sell, it meant people

didn't want to know about John and Yoko - either

they didn't want John anymore or they didn't want

John with Yoko or maybe they just wanted Yoko,

whatever. But if they didn't want the two of us,

we weren't interested. Throughout my career, I've

selected to work with - for more than a one-night

stand, say, with David Bowie or Elton John - only

two people: Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono. I brought

Paul into the original group, the Quarrymen; he

brought George in and George brought Ringo in.

And the second person who interested me as an

artist and somebody I could work with was Yoko

Ono. That ain't bad picking."

When

we arrive at the studio, the engineers being playing

tapes of Yoko's "Kiss Kiss Kiss," "Every

Man Has a Woman Who Loves Him" (both from

Double Fantasy) and a powerful new disco song

(not on the album) called "Walking on Thin

Ice," which features a growling guitar lick

by Lennon, based on Sanford Clark's 1956 song,

"The Fool."

Which

way could I come back into this game?" John

asks as we settle down. "I came back from

the place I know best - as unpretentiously as

possible - not to prove anything but just to enjoy

it."

"I've

heard that you've had a guitar on the wall behind

your bed for the past five or six years, and that

you've only taken it down and played it for Double

Fantasy. Is that true?"

"I

bought this beautiful electric guitar, round about

the period I got back with Yoko and had the baby,"

John explains. "It's not a normal guitar;

it doesn't have a body; it's just an arm and this

tubelike, toboggan-looking thing, and you can

lengthen the top for the balance of it if you're

sitting or standing up. I played it a little,

then just hung it up behind the bed, but I'd look

at it every now and then, because it had never

done a professional thing, it had never really

been played. I didn't want to hide it the way

one would hide an instrument because it was too

painful to look at - like, Artie Shaw went through

a big thing and never played again. But I used

to look at it and think, 'Will I ever pull it

down?'

"Next

to it on the wall I'd placed the number 9 and

a dagger Yoko had given me - a dagger made out

of a bread knife from the American Civil War to

cut away the bad vibes, to cut away the past symbolically.

It was just like a picture that hangs there but

you never really see, and then recently I realized,

'Oh, goody! I can finally find out what this guitar

is all about,' and I took it down and used it

in making Double Fantasy.

"All

through the taping of 'Starting Over,' I was calling

what I was doing 'Elvis Orbison': 'I want you

I need only the lonely.' I'm a born-again rocker,

I feel that refreshed, and I'm going right back

to my roots. It's like Dylan doing Nashville Skyline,

except I don't have any Nashville, you know, being

from Liverpool. So I go back to the records I

know - Elvis and Roy Orbison and Gene Vincent

and Jerry Lee Lewis. I occasionally get ripped

off into 'Walruses' or 'Revolution 9,' but my

far-out side has been completely encompassed by

Yoko.

"The

first show we did together was at Cambridge University

in 1968 or '69, when she had been booked to do

a concert with some jazz musicians. That was the

first time I had appeared un-Beatled. I just hung

around and played feedback, and people got very

upset because they recognized me: 'What's he doing

here?' It's always: 'Stay in your bag.' So, when

she tried to rock, they said, 'What's she doing

here?' And when I went with her and tried to be

the instrument and not project - to just be her

band, like a sort of like Turner to her Tina,

only her Tina was a different, avant-garde Tina

- well, even some of the jazz guys got upset.

"Everybody

has pictures they want you to live up to. But

that's the same as living up to your parents'

expectations, or to society's expectations, or

to so-called critics who are just guys with a

typewriter in a little room, smoking and drinking

beer and having their dreams and nightmares, too,

but somehow pretending that they're living in

a different, separate world. That's all right.

But there are people who break out of their bags."

"I

remember years ago," I say, "when you

and Yoko appeared in bags at a Vienna press conference."

"Right.

We sang a Japanese folk song in the bags. 'Das

ist really you, John? John Lennon in zee bag?'

Yeah, it's me. 'But how do we know ist you?' Because

I'm telling you. 'Vy don't you come out from this

bag?' Because I don't want to come out of the

bag. 'Don't you realize this is the Hapsburg palace?'

I thought it was a hotel. 'Vell, it is now a hotel.'

They had great chocolate cake in that Viennese

hotel, I remember that. Anyway, who wants to be

locked in a bag? You have to break out of your

bag to keep alive."

"In

'Beautiful Boys,' " I add, "Yoko sings:

'Please never be afraid to cry . . . / Don't ever

be afraid to fly . . . / Don't be afraid to be

afraid.' "

"Yes,

it's beautiful. I'm often afraid, and I'm not

afraid to be afraid, though it's always scary.

But it's more painful to try not to be yourself.

People spend a lot of time trying to be somebody

else, and I think it leads to terrible diseases.

Maybe you get cancer or something. A lot of tough

guys die of cancer, have you noticed? Wayne, McQueen.

I think it has something to do - I don't know,

I'm not an expert - with constantly living or

getting trapped in an image or an illusion of

themselves, suppressing some part of themselves,

whether it's the feminine side or the fearful

side.

"I'm

well aware of that, because I come from the macho

school of pretense. I was never really a street

kid or a tough guy. I used to dress like a Teddy

boy and identify with Marlon Brando and Elvis

Presley, but I was never really in any street

fights or down-home gangs. I was just a suburban

kid, imitating the rockers. But it was a big part

of one's life to look tough. I spent the whole

of my childhood with shoulders up around the top

of me head and me glasses off because glasses

were sissy, and walking in complete fear, but

with the toughest-looking little face you've ever

seen. I'd get into trouble just because of the

way I looked; I wanted to be this tough James

Dean all the time. It took a lot of wrestling

to stop doing that. I still fall into it when

I get insecure. I still drop into that I'm-a-street-kid

stance, but I have to keep remembering that I

never really was one."

"Carl

Jung once suggested that people are made up of

a thinking side, a feeling side, an intuitive

side and a sensual side," I mention. "Most

people never really develop their weaker sides

and concentrate on the stronger ones, but you

seem to have done the former."

"I

think that's what feminism is all about,"

John replies. "That's what Yoko has taught

me. I couldn't have done it alone; it had to be

a female to teach me. That's it. Yoko has been

telling me all the time, 'It's all right, it's

all right.' I look at early pictures of meself,

and I was torn between being Marlon Brando and

being the sensitive poet - the Oscar Wilde part

of me with the velvet, feminine side. I was always

torn between the two, mainly opting for the macho

side, because if you showed the other side, you

were dead."

"On

Double Fantasy," I say, "your song 'Woman'

sounds a bit like a troubadour poem written to

a medieval lady."

"

'Woman' came about because, one sunny afternoon

in Bermuda, it suddenly hit me. I saw what women

do for us. Not just what my Yoko does for me,

although I was thinking in those personal terms.

Any truth is universal. If we'd made our album

in the third person and called it Freda and Ada

or Tommy and had dressed up in clown suits with

lipstick and created characters other than us,

maybe a Ziggy Stardust, would it be more acceptable?

It's not our style of art; our life is our art.

. . . Anyway, in Bermuda, what suddenly dawned

on me was everything I was taking for granted.

Women really are the other half of the sky, as

I whisper at the beginning of the song. And it

just sort of hit me like a flood, and it came

out like that. The song reminds me of a Beatles

track, but I wasn't trying to make it sound like

that. I did it as I did 'Girl' many years ago.

So this is the grown-up version of 'Girl.'

"People

are always judging you, or criticizing what you're

trying to say on one little album, on one little

song, but to me it's a lifetime's work. From the

boyhood paintings and poetry to when I die - it's

all part of one big production. And I don't have

to announce that this album is part of a larger

work; if it isn't obvious, then forget it. But

I did put a little clue on the beginning of the

record - the bells . . . the bells on 'Starting

Over.' The head of the album, if anybody is interested,

is a wishing bell of Yoko's. And it's like the

beginning of 'Mother' on the Plastic Ono album,

which had a very slow death bell. So it's taken

a long time to get from a slow church death bell

to this sweet little wishing bell. And that's

the connection. To me, my work is one piece."

"All

the way through your work, John, there's this

incredibly strong notion about inspiring people

to be themselves and to come together and try

to change things. I'm thinking here, obviously,

of songs like 'Give Peace a Chance,' 'Power to

the People' and 'Happy Xmas (War Is Over).' "

"It's

still there," John replies. "If you

look on the vinyl around the new album's [the

twelve-inch single "(Just Like) Starting

Over"] logo - which all the kids have done

already all over the world from Brazil to Australia

to Poland, anywhere that gets the record - inside

is written: ONE WORLD, ONE PEOPLE. So we continue.

"I

get truly affected by letters from Brazil or Poland

or Austria - places I'm not conscious of all the

time - just to know somebody is there, listening.

One kid living up in Yorkshire wrote this heartfelt

letter about being both Oriental and English and

identifying with John and Yoko. The odd kid in

the class. There are a lot of those kids who identify

with us. They don't need the history of rock &

roll. They identify with us as a couple, a biracial

couple, who stand for love, peace, feminism and

the positive things of the world.

"You

know, give peace a chance, not shoot people for

peace. All we need is love. I believe it. It's

damn hard, but I absolutely believe it. We're

not the first to say, 'Imagine no countries' or

'Give peace a chance,' but we're carrying that

torch, like the Olympic torch, passing it from

hand to hand, to each other, to each country,

to each generation. That's our job. We have to

conceive of an idea before we can do it.

"I've

never claimed divinity. I've never claimed purity

of soul. I've never claimed to have the answer

to life. I only put out songs and answer questions

as honestly as I can, but only as honestly as

I can - no more, no less. I cannot live up to

other people's expectations of me because they're

illusionary. And the people who want more than

I am, or than Bob Dylan is, or than Mick Jagger

is. . . .

"Take

Mick, for instance. Mick's put out consistently

good work for twenty years, and will they give

him a break? Will they ever say, 'Look at him,

he's Number One, he's thirty-six and he's put

out a beautiful song, "Emotional Rescue,"

it's up there.' I enjoyed it, lots of people enjoyed

it. So it goes up and down, up and down. God help

Bruce Springsteen when they decide he's no longer

God. I haven't seen him - I'm not a great 'in'-person

watcher - but I've heard such good things about

him. Right now, his fans are happy. He's told

them about being drunk and chasing girls and cars

and everything, and that's about the level they

enjoy. But when he gets down to facing his own

success and growing older and having to produce

it again and again, they'll turn on him, and I

hope he survives it. All he has to do is look

at me and Mick. . . . I cannot be a punk in Hamburg

and Liverpool anymore. I'm older now. I see the

world through different eyes. I still believe

in love, peace and understanding, as Elvis Costello

said, and what's so funny about love, peace and

understanding?"

"There's

another aspect of your work, which has to do with

the way you continuously question what's real

and what's illusory, such as in 'Look at Me,'

your beautiful new 'Watching the Wheels' - what

are those wheels, by the way? - and, of course,

'Strawberry Fields Forever,' in which you sing:

'Nothing is real.' "

"Watching

the wheels?" John asks. "The whole universe

is a wheel, right? Wheels go round and round.

They're my own wheels, mainly. But, you know,

watching meself is like watching everybody else.

And I watch meself through my child, too. Then,

in a way, nothing is real, if you break the word

down. As the Hindus or Buddhists say, it's an

illusion, meaning all matter is floating atoms,

right? It's Rashomon. We all see it, but the agreed-upon

illusion is what we live in. And the hardest thing

is facing yourself. It's easier to shout 'Revolution'

and 'Power to the people' than it is to look at

yourself and try to find out what's real inside

you and what isn't, when you're pulling the wool

over your own eyes. That's the hardest one.

"I

used to think that the world was doing it to me

and that the world owed me something, and that

either the conservatives or the socialists or

the fascists or the communists or the Christians

or the Jews were doing something to me; and when

you're a teenybopper, that's what you think. I'm

forty now. I don't think that anymore, 'cause

I found out it doesn't fucking work! The thing

goes on anyway, and all you're doing is jacking

off, screaming about what your mommy or daddy

or society did, but one has to go through that.

For the people who even bother to go through that

- most assholes just accept what is and get on

with it, right? - but for the few of us who did

question what was going on. . . . I have found

out personally - not for the whole world! - that

I am responsible for it, as well as them. I am

part of them. There's no separation; we're all

one, so in that respect, I look at it all and

think, 'Ah, well, I have to deal with me again

in that way. What is real? What is the illusion

I'm living or not living?' And I have to deal

with it every day. The layers of the onion. But

that is what it's all about.

"The

last album I did before Double Fantasy was Rock

'n' Roll, with a cover picture of me in Hamburg

in a leather jacket. At the end of making that

record, I was finishing up a track that Phil Spector

had made me sing called 'Just Because,' which

I really didn't know - all the rest I'd done as

a teenager, so I knew them backward - and I couldn't

get the hang of it. At the end of that record

- I was mixing it just next door to this very

studio - I started spieling and saying, 'And so

we say farewell from the Record Plant,' and a

little thing in the back of my mind said, 'Are

you really saying farewell?' I hadn't thought

of it then. I was still separated from Yoko and

still hadn't had the baby, but somewhere in the

back was a voice that was saying, 'Are you saying

farewell to the whole game?'

"It

just flashed by like that - like a premonition.

I didn't think of it until a few years later,

when I realized that I had actually stopped recording.

I came across the cover photo - the original picture

of me in my leather jacket, leaning against the

wall in Hamburg in 1962 - and I thought, 'Is this

it? Do I start where I came in, with "Be-Bop-A-Lula"?'

The day I met Paul I was singing that song for

the first time onstage. There's a photo in all

the Beatles books - a picture of me with a checked

shirt on, holding a little acoustic guitar - and

I am singing 'Be-Bop-A-Lula,' just as I did on

that album, and there's a picture in Hamburg and

I'm saying goodbye from the Record Plant.

"Sometimes

you wonder, I mean really wonder. I know we make

our own reality and we always have a choice, but

how much is preordained? Is there always a fork

in the road and are there two preordained paths

that are equally preordained? There could be hundreds

of paths where one could go this way or that way

- there's a choice and it's very strange sometimes.

. . . And that's a good ending for our interview."

Jack

Douglas, coproducer of Double Fantasy, has arrived

and is overseeing the mix of Yoko's songs. It's

2:30 in the morning, but John and I continue to

talk until four as Yoko naps on a studio couch.

John speaks of his plans for touring with Yoko

and the band that plays on Double Fantasy; of

his enthusiasm for making more albums; of his

happiness about living in New York City, where,

unlike England or Japan, he can raise his son

without racial prejudice; of his memory of the

first rock & roll song he ever wrote (a takeoff

on the Dell Vikings' "Come Go with Me,"

in which he changed the lines to: "Come come

come come / Come and go with me / To the peni-tentiary");

of the things he has learned on his many trips

around the world during the past five years. As

he walks me to the elevator, I tell him how exhilarating

it is to see Yoko and him looking and sounding

so well. "I love her, and we're together,"

he says. "Goodbye, till next time."

"After

all is really said and done / The two of us are

really one," John Lennon sings in "Dear

Yoko," a song inspired by Buddy Holly, who

himself knew something about true love's ways.

"People asking questions lost in confusion

/ Well I tell them there's no problem, only solutions,"

sings John in "Watching the Wheels,"

a song about getting off the merry-go-round, about

letting it go.

In

the tarot, the Fool is distinguished from other

cards because it is not numbered, suggesting that

the Fool is outside movement and change. And as

it has been written, the Fool and the clown play

the part of scapegoats in the ritual sacrifice

of humans. John and Yoko have never given up being

Holy Fools. In a recent Playboy interview, Yoko,

responding to a reference to other notables who

had been interviewed in that magazine, said: "People

like Carter represent only their country. John

and I represent the world." I am sure many

readers must have snickered. But three nights

after our conversation, the death of John Lennon

revealed Yoko's statement to be astonishingly

true. "Come together over me," John

had sung, and people everywhere in the world came

together.

Source:

http://RollingStone.com

1980

Playboy Interview

With John Lennon And Yoko Ono

by David Sheff

1975

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Pete Hamill

1968

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Jonathan Cott

'Man

of the Decade'

Interview With John Lennon

|