|

1968

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Jonathan Cott

September 28, 1968

Published November 23, 1968

Two

Other Rolling Stone Interviews

With John Lennon

1980

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Jonathan Cott

1975

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Pete Hamill

Q:

"I've listed a group of songs that I associate

with you, in terms of what you are or what you

were, songs that struck me as embodying you a

little bit: 'You've Got To Hide Your Love Away,'

'Strawberry Fields,' 'It's Only Love,' 'She Said

She Said,' 'Lucy in the Sky,' 'I'm Only Sleeping,'

'Run for Your Life,' 'I Am the Walrus,' 'All You

Need Is Love,' 'Rain,' 'Girl.'"

JOHN

"The ones that really meant something to

me... Look, I don't know about 'Hide Your Love

Away,' that's so long ago. Probably 'Strawberry

Fields,' 'She Said,' 'Walrus,' 'Rain,' 'Girl,'

there are just one or two others, 'Day Tripper,'

'Paperback Writer,' even. 'Ticket To Ride' was

one more, I remember that. It was a definite sort

of change. 'Norwegian Wood' ...that was the sitar

bit. Definitely, I consider them moods or moments."

Q:

"There have been a lot of philosophical analyses

written about your songs, 'Strawberry Fields,'

in particular..."

JOHN:

"Well, they can take them apart. They can

take anything apart. I mean, I hit it on all levels,

you know. We write lyrics, and I write lyrics

that you don't realize what they mean till after.

Especially some of the better songs or some of

the more flowing ones, like 'Walrus.' The whole

first verse was written without any knowledge.

And 'Tomorrow Never Knows' ...I didn't know what

I was saying, and you just find out later. I know

that when there are some lyrics I dig I know that

somewhere people will be looking at them. And

I dig the people that notice that I have a sort

of strange rhythm scene, because I've never been

able to keep rhythm on the stage. I always used

to get lost. It's me double off-beats."

Q:

"What is Strawberry Fields?"

JOHN

"It's a name, it's a nice name. When I was

writing 'In My Life,' I was trying 'Penny Lane'

at that time. We were trying to write about Liverpool,

and I just listed all the nice-sounding names,

just arbitrarily. Strawberry Fields was a place

near us that happened to be a Salvation Army home.

But Strawberry Fields-- I mean, I have visions

of Strawberry Fields. And there was Penny Lane,

and the Cast Iron Shore, which I've just got in

some song now, and they were just good names--

just groovy names. Just good sounding. Because

Strawberry Fields is anywhere you want to go."

Q:

"Pop analysts are often trying to read something

into songs that isn't there."

JOHN:

"It is there. It's like abstract art really.

It's just the same really. It's just that when

you have to think about it to write it, it just

means that you labored at it. But when you just

say it, man, you know you're saying it, it's a

continuous flow. The same as when you're recording

or just playing. You come out of a thing and you

know 'I've been there,' and it was nothing, it

was just pure, and that's what we're looking for

all the time, really."

Q:

"How much do you think the songs go toward

building up a myth of a state of mind?"

JOHN:

"I don't know. I mean, we got a bit pretentious.

Like everybody, we had our phase and now it's

a little change over to trying to be more natural,

less 'newspaper taxis,' say. I mean, we're just

changing. I don't know what we're doing at all,

I just write them. Really, I just like rock &

roll. I mean, these..." (pointing to a pile

of Fifties records) "...are the records I

dug then, I dig them now and I'm still trying

to reproduce 'Some Other Guy' sometimes. or 'Be-Bop-A-Lula.'

Whatever it is, it's the same bit for me. It's

really just the sound."

Q:

"The Beatles seem to be one of the only groups

who ever made a distinction between friends and

lovers. For instance, there's 'baby' who can drive

your car. But when it comes to 'We Can Work It

Out,' you talk about 'my friend.' In most other

groups' songs, calling someone 'baby' is a bit

demeaning compared to your distinction."

JOHN

"Yeah, I don't know why. It's Paul's bit

that... 'Buy you a diamond ring, my friend' ...it's

an alternative to 'baby.' You can take it logically,

the way you took it. See, I don't know really.

Yours is as true a way of looking at it as any

other way. In 'Baby, You're a Rich Man' the point

was, stop moaning. You're a rich man and we're

all rich men, heh, heh, baby!"

Q:

"I've felt your other mood recently: 'Here

I stand, head in hand' in 'You've Got To Hide

Your Love Away,' and 'When I was a boy, everything

was right' in 'She Said She Said.'"

JOHN:

"Yeah, right. That was pure. That was what

I meant all right. You see, when I wrote that

I had the 'She said she said,' but it was just

meaning nothing. It was just vaguely to do with

someone who had said something like he knew what

it was like to be dead, and then it was just a

sound. And then I wanted a middle-eight. The beginning

had been around for days and days and so I wrote

the first thing that came into my head and it

was 'When I was a boy,' in a different beat, but

it was real because it just happened. It's funny,

because while we're recording we're all aware

and listening to our old records and we say, we'll

do one like 'The Word' ...make it like that. It

never does turn out like that, but we're always

comparing and talking about the old albums-- just

checking up. What is it... like swatting up for

the exam-- just listening to everything."

Q:

"Yet people think you're trying to get away

from the old records."

JOHN:

"But I'd like to make a record like 'Some

Other Guy.' I haven't done one that satisfies

me as much as that satisfied me. Or 'Be-Bop-A-Lula'

or 'Heartbreak Hotel' or 'Good Golly, Miss Molly'

or 'Whole Lot of Shakin.' I'm not being modest.

I mean, we're still trying it. We sit there in

the studio and we say, 'How did it go, how did

it go? Come on, let's do that.' Like what Fats

Domino has done with 'Lady Madonna'-- 'See how

they ruhhnnn.'"

Q:

"Wasn't it about the time of 'Rubber Soul'

that you moved away from the old records to something

quite different?"

JOHN:

"Yes, yes, we got involved completely in

ourselves then. I think it was 'Rubber Soul' when

we did all our own numbers. Something just happened.

We controlled it a bit. Whatever it was we were

putting over, we just tried to control it a bit."

Q:

"Are there any other versions of your songs

you like?"

JOHN:

"Well, Ray Charles' version of 'Yesterday'

...that's beautiful. And 'Eleanor Rigby' is a

groove. I just dig the strings on that. Like Thirties

strings. Jose Feliciano does great things to 'Help!'

and 'Day Tripper.'"

"'Got

To Get You Into My Life.' Sure, we were doing

our Tamla Motown bit. You see, we're influenced

by whatever's going. Even if we're not influenced,

we're all going that way at a certain time. If

we played a Stones record now, and a Beatles record--

and we've been apart-- you'd find a lot of similarities.

We're all heavy. Just heavy. How did we ever do

anything light? What we're trying to do is rock

'n roll, with less of your philosorock, is what

we're saying to ourselves. And get on with rocking

because rockers is what we really are. You can

give me a guitar, stand me up in front of a few

people. Even in the studio, if I'm getting into

it, I'm just doing my old bit-- not quite doing

Elvis Legs but doing my equivalent. It's just

natural. Everybody says we must do this and that

but our thing is just rocking, you know, the usual

gig. That's what this new record ('The White Album')

is about. Definitely rocking. What we were doing

on Pepper was rocking-- and not rocking."

"'A

Day in the Life'-- that was something. I dug it.

It was a good piece of work between Paul and me.

I had the 'I read the news today' bit, and it

turned Paul on. Now and then we really turn each

other on with a bit of song, and he just said

'yeah'-- bang bang, like that. It just sort of

happened beautifully, and we arranged it and rehearsed

it, which we don't often do, the afternoon before.

So we all knew what we were playing, we all got

into it. It was a real groove, the whole scene

on that one. Paul sang half of it and I sang half.

I needed a middle-eight for it, but that would

have been forcing it. All the rest had come out

smooth, flowing, no trouble, and to write a middle-eight

would have been to write a middle-eight, but instead

Paul already had one there. It's a bit of 2001,

you know."

Q:

"Songs like 'Good Morning, Good Morning'

and 'Penny Lane' convey a child's feeling of the

world."

JOHN:

"We write about our past. 'Good Morning,

Good Morning,' I was never proud of it. I just

knocked it off to do a song. But it was writing

about my past so it does get the kids because

it was me at school, my whole bit. The same with

'Penny Lane.' We really got into the groove of

imagining Penny Lane-- the bank was there, and

that was where the tram sheds were and people

waiting and the inspector stood there, the fire

engines were down there. It was just reliving

childhood."

Q:

"You really had a place where you grew up!"

JOHN:

"Oh, yeah. Didn't you?"

Q:

"Well, Manhattan isn't Liverpool."

JOHN:

"Well, you could write about your local bus

station."

Q:

"In Manhattan?"

JOHN:

"Sure, why not? Everywhere is somewhere."

Q:

"In 'Hey Jude,' as in one of your first songs,

'She Loves You,' you're singing to someone else

and yet you might as well be singing to yourself.

Do you find that as well?"

JOHN:

"Oh, yeah. Well, when Paul first sang 'Hey

Jude' to me... or played me the little tape he'd

made of it... I took it very personally. 'Ah,

it's me,' I said, 'It's me.' He says, 'No, it's

me.' I said, 'Check. We're going through the same

bit.' So we all are. Whoever is going through

a bit with us is going through it, that's the

groove."

Q:

"In the 'Magical Mystery Tour' theme song

you say, 'The Magical Mystery Tour is waiting

to take you away.' In 'Sgt. Pepper' you sing,

'We'd like to take you home with us.' How do you

relate this embracing, 'come sit down on my lawn'

feeling in the songs with your need for everyday

privacy?"

JOHN:

"I take a narrower concept of it, like whoever

was around at the time wanting to talk to them

talked to me, but of course it does have that

wider aspect to it. The concept is very good and

I went through it and said, 'Well, okay. Let them

sit on my lawn.' But of course it doesn't work.

People climbed in the house and smashed things

up, and then you think, 'That's no good, that

doesn't work.' So actually you're saying, 'Don't

talk to me,' really. We're all trying to say nice

things like that but most of the time we can't

make it-- ninety percent of the time-- and the

odd time we do make it, when we do it, together

as people. You can say it in a song: 'Well, whatever

I did say to you that day about getting out of

the garden, part of me said that but, really,

in my heart of hearts, I'd like to have it right

and talk to you and communicate.' Unfortunately

we're human, you know-- it doesn't seem to work."

Q:

"Do you feel free to put anything in a song?"

JOHN:

"Yes. In the early days I'd... well, we all

did... we'd take things out for being banal cliches,

even chords we wouldn't use because we thought

they were cliches. And even just this year there's

been a great release for all of us, going right

back to the basics. On 'Revolution' I'm playing

the guitar and I haven't improved since I was

last playing, but I dug it. It sounds the way

I wanted it to sound. It's a pity I can't do it

better... the fingering, you know... but I couldn't

have done that last year. I'd have been too paranoiac.

I couldn't play: ('Revolution' guitar intro) 'dddddddddddddd.'

George must play, or somebody better. My playing

has probably improved a little bit on this session

because I've been playing a little. I was always

the rhythm guitar anyway, but I always just fiddled

about in the background. I didn't actually want

to play rhythm. We all sort of wanted to be lead--

as in most groups - but it's a groove now, and

so are the cliches. We've gone past those days

when we wouldn't have used words because they

didn't make sense, or what we thought was sense.

But of course Dylan taught us a lot in this respect."

"Another

thing is, I used to write a book or stories on

one hand and write songs on the other. And I'd

be writing completely free form in a book or just

on a bit of paper, but when I'd start to write

a song I'd be thinking: dee duh dee duh do doo

do de do de doo. And it took Dylan and all that

was going on then to say, 'oh, come on now, that's

the same bit, I'm just singing the words.' With

'I Am the Walrus,' I had 'I am he as you are he

as we are all together.' I had just these two

lines on the typewriter, and then about two weeks

later I ran through and wrote another two lines

and then, when I saw something, after about four

lines, I just knocked the rest of it off. Then

I had the whole verse or verse and a half and

then sang it. I had this idea of doing a song

that was a police siren, but it didn't work in

the end (sings like a siren) 'I-am-he-as-you-are-he-as...'

You couldn't really sing the police siren."

Q:

"Do you write your music with instruments

or in your head?"

JOHN:

"On piano or guitar. Most of this session

has been written on guitar 'cuz we were in India

and only had our guitars there. They have a different

feel about them. I missed the piano a bit because

you just write differently. My piano playing is

even worse than me guitar. I hardly know what

the chords are, so it's good to have a slightly

limited palette, heh heh."

Q:

"What did you think of Dylan's version of

'Norwegian Wood'?"

JOHN:

"I was very paranoid about that. I remember

he played it to me when he was in London. He said,

'What do you think?' I said, 'I don't like it.'

I didn't like it. I was very paranoid. I just

didn't like what I felt I was feeling-- I thought

it was an out-and-out skit, you know, but it wasn't.

It was great. I mean, he wasn't playing any tricks

on me. I was just going through the bit."

Q:

"Is there anybody besides Dylan you've gotten

something from musically?"

JOHN:

"Oh, millions. All those I mentioned before...

Little Richard, Presley."

Q:

"Anyone contemporary?"

JOHN:

"Are they dead? Well, nobody sustains it.

I've been buzzed by the Stones and other groups,

but none of them can sustain the buzz for me continually

through a whole album or through three singles

even."

Q:

"You and Dylan are often thought of together

in the same way."

JOHN:

"Yeah? Yeah, well we were for a bit, but

I couldn't make it. Too paranoiac. I always saw

him when he was in London. He first turned us

on in New York actually. He thought 'I Want to

Hold Your Hand' - when it goes 'I can't hide'

- he thought we were singing 'I get high.' So

he turns up with Al Aronowitz and turns us on,

and we had the biggest laugh all night - forever.

Fantastic. We've got alot to thank him for."

Q:

"Do you ever see him anymore?"

JOHN

"No, 'cuz he's living his cozy little life,

doing that bit. If I was in New York, he'd be

the person I'd most like to see. I've grown up

enough to communicate with him. Both of us were

always uptight, you know, and of course I wouldn't

know whether he was uptight, because I was so

uptight. And then, when he wasn't uptight, I was...

all that bit. But we just sat it out because we

just liked being together."

Q:

"What about the new desire to return to a

more natural environment? Dylan's return to country

music?"

JOHN:

"Dylan broke his neck and we went to India.

Everybody did their bit. And now we're all just

coming out, coming out of a shell, in a new way,

kind of saying, remember what it was like to play."

Q:

"Do you feel better now?"

JOHN:

"Yes... and worse."

Q:

"What do you feel about India now?"

JOHN:

"I've got no regrets at all, 'cuz it was

a groove and I had some great experiences meditating

eight hours a day-- some amazing things, some

amazing trips-- it was great. And I still meditate

off and on. George is doing it regularly. And

I believe implicitly in the whole bit. It's just

that it's difficult to continue it. I lost the

rosy glasses. And I'm like that. I'm very idealistic.

So I can't really manage my exercises when I've

lost that. I mean, I don't want to be a boxer

so much. It's just that a few things happened,

or didn't happen. I don't know, but something

happened. It was sort of like (snaps fingers)

and we just left and I don't know what went on.

It's too near-- I don't really know what happened."

Q:

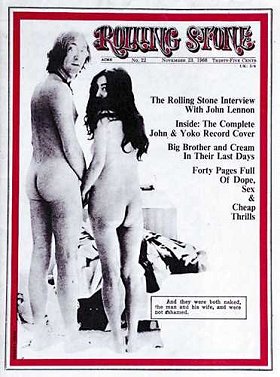

"You just showed me what might be the front

and back album photos for the record you're putting

out of the music you and Yoko composed for your

film 'Two Virgins.' The photos have the simplicity

of a daguerreotype..."

JOHN:

"Well, that's because I took it. I'm a ham

photographer, you know. It's me Nikon what I was

given by a commercially-minded Japanese when we

were in Japan, along with me Pentax, me Canon,

me boom-boom and all the others. So I just set

it up and did it."

Q:

"For the cover, there's a photo of you and

Yoko standing naked facing the camera. And on

the backside are your backsides. What do you think

people are going to think of the cover?"

JOHN:

"Well, we've got that to come. The thing

is, I started it with a pure... it was the truth,

and it was only after I'd got into it and done

it and looked at it that I'd realized what kind

of scene I was going to create. And then suddenly,

there it was, and then suddenly you show it to

people and then you know what the world's going

to do to you, or try to do. But you have no knowledge

of it when you conceive it or make it. Originally,

I was going to record Yoko, and I thought the

best picture of her for an album would be her

naked. I was just going to record her as an artist.

We were only on those kind of terms then. So after

that, we got together, it just seemed natural

for us, if we made an album together, for both

of us to be naked. Of course, I've never seen

me prick on an album or on a photo before: 'What-on-earth,

there's a fellow with his prick out.' And that

was the first time I realized me prick was out,

you know. I mean, you can see it on the photo

itself - we're naked in front of a camera - that

comes over in the eyes, just for a minute you

go!! I mean, you're not used to it, being naked,

but it's got to come out."

Q:

"How do you face the fact that people are

going to mutilate you?"

JOHN:

"Well, I can take that as long as we can

get the cover out. And I really don't know what

the chances are of that."

Q:

"You don't worry about the nuts across the

street?

JOHN:

"No, no. I know it won't be very comfortable

walking around with all the lorry drivers whistling

and that, but it'll all die. Next year it'll be

nothing, like miniskirts or bare tits. It isn't

anything. We're all naked really. When people

attack Yoko and me, we know they're paranoiac.

We don't worry too much. It's the ones that don't

know, and you know they don't know-- they're just

going round in a blue fuzz. The thing is, the

album also says: 'Look, lay off will you? It's

two people - what have we done?'"

Q:

"Lenny Bruce once compared himself to a doctor,

saying that if people weren't sick, there wouldn't

be any need for him."

JOHN:

"That's the bit, isn't it? Since we started

being more natural in public, the four of us,

we've really had a lot of knocking. I mean, we're

always natural. I mean, you can't help it. We

couldn't have been where we are if we hadn't done

that. We wouldn't have been us either. And it

took four of us to enable us to do it; we couldn't

have done it alone and kept that up. I don't know

why I get knocked more often. I seem to open me

mouth more often, something happens, I forget

what I am till it all happens again. I mean, we

just get knocked, from the underground... the

pop world... me personally. They're all doing

it. They've got to stop soon."

Q:

"Couldn't you go off to your own community

and not be bothered with all of this?"

JOHN:

"Well, it's just the same there, you see.

India was a bit of that, it was a taste of it.

It's the same. So there's a small community, it's

the same gig, it's relative. There's no escape."

Q:

"Your show at the Fraser Gallery gave critics

a chance to take a swipe at you."

JOHN:

"Oh, right, but putting it on was taking

a swipe at them in a way. I mean, that's what

it was about. What they couldn't understand was

that - a lot of them were saying, 'well, if it

hadn't been for John Lennon nobody would have

gone to it,' but as it was, it was me doing it.

And if it had been Sam Bloggs it would have been

nice. But the point of it was - it was me. And

they're using that as a reason to say why it didn't

work. Work as what?"

Q:

"Do you think Yoko's film of you smiling

would work if it were just anyone smiling?"

JOHN:

"Yes, it works with somebody else smiling,

but she went through all this. It originally started

out that she wanted a million people all over

the world to send in a snapshot of themselves

smiling, and then it got down to lots of people

smiling, and then maybe one or two and then me

smiling as a symbol of today smiling - and that's

what I am, whatever that means. And so it's me

smiling, and that's the hang-up, of course, because

it's me again. But they've got to see it someday...

it's only me. I don't mind if people go to the

film to see me smiling because it doesn't matter,

it's not harmful. The idea of the film won't really

be dug for another fifty or a hundred years probably.

That's what it's all about. I just happen to be

that face."

Q:

"It's too bad people can't come down here

individually to see how you're living."

JOHN:

"Well, that's it. I didn't see Ringo and

his wife for about a month when I first got together

with Yoko, and there were rumors going around

about the film and all that. Maureen was saying

she really had some strange ideas about where

we were at and what we were up to. And there were

some strange reactions from all me friends and

at Apple about Yoko and me and what we were doing--

'Have they gone mad?' But of course it was just

us, you know, and if they are puzzled or reacting

strangely to us two being together and doing what

we're doing, it's not hard to visualize the rest

of the world really having some amazing image."

Q:

"'International Times' recently published

an interview with Jean-Luc Godard..."

JOHN:

"Oh yeah, right, he said we should do something.

Now that's sour grapes from a man who couldn't

get us to be in his film..." ('One Plus One,'

in which the Stones appear) "...and I don't

expect it from people like that. Dear Mr. Godard,

just because we didn't want to be in the film

with you, it doesn't mean to say that we aren't

doing any more than you. We should do whatever

we're all doing."

Q:

"But Godard put it in activist political

terms. He said that people with influence and

money should be trying to blow up the establishment

and that you weren't."

JOHN:

"What's he think we're doing? He wants to

stop looking at his own films and look around.

'Time Magazine' came out and said, look, the Beatles

say 'no' to destruction. There's no point in dropping

out because it's the same there and it's got to

change. But I think it all comes down to changing

your head and, sure, I know that's a cliche."

Q:

"What would you tell a black-power guy who's

changed his head and then finds a wall there all

the time?"

JOHN:

"Well, I can't tell him anything 'cuz he's

got to do it himself. If destruction's the only

way he can do it, there's nothing I can say that

could influence him 'cuz that's where he's at,

really. We've all got that in us, too, and that's

why I did the 'Out, and In' bit on a few takes

and in the TV version of 'Revolution'-- 'Destruction,

well, you know, you can count me out, and in,'

like yin and yang. I prefer 'out.' But we've got

the other bit in us. I don't know what I'd be

doing if I was in his position. I don't think

I'd be so meek and mild. I just don't know."

Source:

http://RollingStone.com

1980

Playboy Interview

With John Lennon And Yoko Ono

by David Sheff

1980

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Jonathan Cott

1975

Rolling Stone Interview

With John Lennon

by Pete Hamill

'Man

of the Decade'

Interview With John Lennon

|